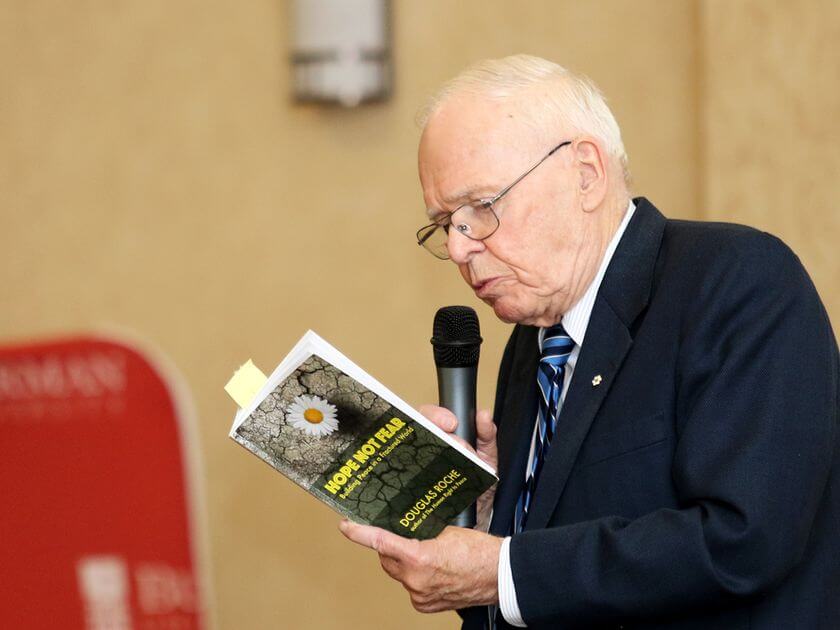

The Heart of Doug Roche: Creative Dissent – PART II

Cesar Jaramillo (Edited by Windy Stocker)

Volume 38 Issue 10, 11, & 12 | Posted: December 29, 2023

CJ (Cesar Jaramillo): Consider Canada – the country, the government. Is Canada pulling its weight? In these dangerous times, could Canada be doing more?

DR (Doug Roche): If you look at a map of the world, you see a great huge section of it called Canada and huge sections called Russia and China. Canada is the second-largest land space in the world. It’s true that we’re only one-half of one per cent of the population of the world – 38 million of 8 billion people. So we should have no delusions of grandeur, but we should accept some responsibility.

In my view, we are not living up to that responsibility. We have so much: our freedom, liberty, our ability to use opportunities. God has blessed Canada enormously.

I do not wish to create the impression that Canada would solve the crises of the world if it opened its doors and took in millions of immigrants and refugees. We’d be in chaos. But we need to do much more to solve the problems of the world so that not as many people are destitute and forced to find a new place to live because of poverty, the climate crisis, wars. Canada should have the United Nations as the centre of its foreign policy. The UN came into existence to resolve such problems and it should play a much stronger role.

For a long time, Canada’s foreign policy was based on the United States and the United Nations. The UN was considered the vehicle by which we reached out to the world. We sent our best people there. Today, we’re not doing that. Canada has now succumbed to the lure of being a member of the G7 and G20, which are discriminatory clubs. We are now under the sway of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a military alliance.

Yet the enlargement of NATO has itself been a strong factor in causing the conditions that have led to the present war. While I condemn Putin’s aggressive invasion of Ukraine, I must acknowledge that enlarging NATO to the degree that it encircled Russia and kept on encircling it has increased the paranoia of Russia. In 1992, I went to a conference at the Carter Center in the United States on the question of the enlargement of NATO. There I argued that NATO should not expand; however, if it did expand, it should take in Russia. I wouldn’t say that I was laughed out of the room, but my proposal was not adopted.

We’ve got to avoid World War III. It’s true that the use of nuclear weapons will lead to World War III. But we can get to World War III without nuclear weapons, as more and more countries pile in behind NATO and NATO takes a more aggressive position. The situation could evolve into a war between NATO and Russia. That will be World War III, with its heightened risk of nuclear weapons.

CJ: I share your view on the expansion of NATO. However, nuance is lacking in many analyses today. Solidarity with Ukraine has left people with black-and-white visions of the conflict, even though there are many factors at play. Is there a way out of this mess, including a defusing of the nuclear possibility?

DR: I think an international commission, very high level, in which the United Nations plays a significant role. I would like to look to the Security Council, but as the Security Council is blocked by the instigator of the war, we’ve got to go around it. Also, we should not underestimate the influence of China. China wants this war to end.

All wars end, usually in negotiations. It’s better for a war to end sooner than later. The number of people being killed is horrendous and the suffering extends into the developing world. I don’t like the NATO focus on beating Russia. There can be no real winner.

CJ: It sounds like a slow-motion train wreck. I share your fear. I sometimes get the impression that the international community will draw all the wrong conclusions from this crisis. Rather than doing everything to avoid conflict, both sides will redouble on arming and just increase the risk.

DR: Pragmatically speaking, I think that the Biden group and the Putin group recognize that such a war is not in their interests. As for Putin’s launching nuclear weapons, as you well know, it’s not a simple matter of pushing a button. He’s got to go through procedures and chains of command. I count on those guys stopping him.

CJ: If there can be a silver lining to this crisis, it’s that it brings to the fore the insanity of these nuclear deterrence-based policies by verbalizing them. We knew that Russia would consider a first nuclear-weapon strike before Putin said it. We knew that the West reserved the right to retaliate. Maybe humanity is now being confronted with the ugliness of nuclear deterrence.

DR: The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) is right when it outlaws the possession of nuclear weapons, not only the use. Possession of such weapons is an immoral act and, consequently, nuclear deterrence is an immoral doctrine.

CJ: I want to bring NATO and Canada together with a question on Canada’s stand on nuclear disarmament. You’ve said that NATO is a strong influence on Canada. My impression is that Canadian foreign policy is most closely aligned with some U.S. policies and those of its nuclear-armed allies, while the rest of the international community is demanding more concrete progress toward nuclear abolition. Many of those in the rest of the international community have rallied around the recent TPNW; Canada has not. Are you frustrated with Canada’s position?

DR: I’m tied up in knots. People like me are called idealists, but I maintain that I’m a realist. I’m a realist for peace. Idealists think that they can keep the present unfair, unjust, and militaristic system going without a great calamity. Realists believe that there are practical approaches to solving the world’s problems, including climate change (the Paris agreement), the abolition of nuclear weapons (the Non-Proliferation Treaty on Nuclear Weapons [NPT]), and economic and social disparities (the Sustainable Development Goals). We need to put all our political energy and capital and money into solving these and other problems. But we don’t.

Canada’s track record in international development is abysmal. It has almost no involvement in peacekeeping. It has so far rejected the TPNW. Still, its position has evolved. Canada has moved from rejecting the treaty to declaring that it understands the reasons for the treaty. Canada would have supported the final document of the recent Review Conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, had it been successful. It at least acknowledged the existence of the TPNW.

But if you consider that the P5 of the Security Council, the ones charged with peace and security, are the ones who have nuclear weapons, won’t give them up. and reject a treaty that wants to prohibit them, then you can judge where we are.

CJ: Could Canada challenge that reality or would it be too costly?

DR: Yes, Canada should challenge this present cartel on nuclear weapons. I maintain that it would not be costly. When Pierre Trudeau went around the world in 1983, challenging the P5 to slow down the nuclear arms race, he didn’t have to pay a price. As a matter of fact, he was praised by the international community. When Prime Minister Jean Chrétien said no to Canada’s joining the Americans’ war on Iraq, there were no repercussions, no economic penalties. The same was true when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney informed the United States that Canada would not join SDI (Strategic Defense Initiative or Star Wars).

It’s a myth that Canada can’t say boo to the United States without endangering our economic and political relations.

CJ: So what’s the hurdle? There have been overtures to the Canadian government from civil society and progressive governments to do more, to move more quickly, to challenge nuclear weapons possession, to embrace the TPNW. But Canada is just not there.

DR: First, the lack of vision at the highest political levels inhibits expression of vision at the lower levels. Second, the bureaucracy in the Canadian government is structured to work for promotion by not rocking the boat. Such a structure encourages compliance, not innovation.

CJ: Canada’s position on nuclear disarmament has not changed substantially in the last several years, even with the change from a Conservative to a Liberal government. Are there any realistic prospects of changing gears, perhaps initiating a debate within NATO, as the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence has recommended?

DR: Canada wouldn’t even attend the TPNW’s Meeting of States Parties as an observer. We’re influenced by the United States, which is controlled by the military industrial complex. After President Barack Obama got the Nobel Peace Prize for giving a speech in Prague on a nuclear-weapons-free world, he went back to Washington, where the military industrial complex people tightened their chains on him. They locked him down. (My imagery, for literary purposes usually, allows a little exaggeration, but it’s not far from the truth.)

My book on Biden’s ascendancy included quotes from people who said that Biden will not challenge the military industrial complex, which is driving U.S. policy. And that’s what’s dominating us. And we can’t get out from under because we don’t have any leaders who will stand up to it.

CJ: What about small to medium-sized states, like Mexico, Costa Rica, Austria, New Zealand, Ireland, which have embraced the relatively recent humanitarian disarmament movement, and led processes on the TPNW and the arms trade and protection of civilians. Do you find hope in these new players?

DR: Several years ago, the New Agenda Coalition came into existence, led by Ireland and Sweden. This group was meant to gather important middle power states together to advance an agenda that would take nuclear disarmament forward in concrete ways and certainly stood for the abolition of nuclear weapons. It made a significant contribution to the 2010 NPT Review Conference, which was the last successful review conference.

But what happened to the people who led these efforts? Ireland is a very strong player, but the official who really invented the New Agenda Coalition and worked most diligently at it was suddenly transferred to a diplomatic post in France. The Mexican official who stood up to the big powers found himself transferred to Spain. I happen to know that the United States government put pressure on the governments of these two countries to transfer their leading spokespersons out of the field of nuclear disarmament.

Diplomat Alexander Kmentt has the good fortune of working for the Austrian government, which is not subject to this kind of U.S. pressure. So, we’re not without leaders. But most diplomats working in the disarmament field will not rock the boat. They concentrate on such processes as the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative and the Stockholm Initiative. But these initiatives are based on the inevitability of the maintenance of nuclear weapons and seek to mitigate the damage.

CJ: Let’s turn our talk to you as a person. You’re 93 years old. Reflect on your age. Are you anxious about time, about the prospects for nuclear disarmament? Are you at peace with the notion of passing the torch to a new generation?

DR: Thank you, Cesar. I appreciate the way you put the question.

I’m a mix. I’m full of anxiety. I also have peace in my heart. I’m 93; I’ve had a good life. I’m not afraid of dying; I’m afraid of living too long. And I feel that I’ve tried to make a contribution. But I regard myself as one grain of sand on a very large beach. So, I don’t have any delusions of grandeur. I am only one person. I’ll die and people will give me a couple of paragraphs and say he wasn’t that bad a guy and life will go on.

How am I at peace? It’s hard to describe. I’m surrounded by chaos in the world. Is it God who’s guiding me? Is God keeping me alive to write the piece that I just wrote on negotiations in the Ukraine war? Is God keeping me here for a purpose? I feel very blessed that, at 93, I have my physical and my mental health. I’m fortunate.

To the extent that I can, I help people grasp the concepts of love and peace and how we live them and extend them while we’re surrounded by and dealing with chaos. This brings me back to my faith. Faith is, by definition, a mystery. I can’t pretend to explain it all to myself or to you. I know what I’m experiencing and I hope the people I interact with – the people that read this – will know that life is not hopeless.

Humans have more resources and more ability and more knowledge than we ever had before. We have serious problems, but still there is hope. But you have to do something to extend yourself in order to feel it. You can’t just sit down in your chair in your living room and say, now I’m going to be happy and have hope. You’ve got to get out there and do something. A residual effect of exerting yourself beyond yourself gives you more love, peace, and hope.

CJ: Have you found happiness in your life?

DR: In my personal life, definitely. I like good movies and I like good music and I like to entertain my friends. If you lived in Edmonton, you’d be on the guest list for my annual Christmas party, which was interrupted by COVID. My Christmas parties are legendary.

CJ: I was a guest twice at your birthday celebrations in New York. At one, you were going to give remarks and said that your speech was going to be essentially one word. And the word you said was love. Even in this interview, you’ve explicitly referenced love. Why is that essential, even for something as technical as arms control and disarmament?

DR: Jesus said to love one another and love your neighbour as yourself. And the neighbour is the woman in Bangladesh, not just my neighbour across the hall. I just find it a healthier way to live. You can’t go around being mad at everybody and torn with anxiety. Love is such a powerful, driving force. Of course, to love expansively and to love your enemies is very hard. To pray for Mr. Putin is hard.

CJ: And when will Doug Roche stop? Do you ever say, I’ve done more than enough, I deserve a break?

DR: No, never. I stop to rest when I’m tired and hungry, not because I’ve finished my work. Until I can’t, I keep going. I’m happier about myself when I’m working. If you have your health, there’s quite a bit that you can do.

CJ: Can you offer some final thoughts about hope?

DR: The title of my memoir, Creative Dissent, itself reflects hope. Hope relates to the advancement of humanity. We’re on a path toward God. John F. Kennedy used to say, here on Earth, our job is to complete God’s creation. Just the execution of that generates hope. There are lots of avenues that are open to us, whether we’re interested in the environment, in human rights, in disarmament, in economic and social development. Millions upon millions of people are working in those avenues. The cumulative effect of that is to lift up the standards of humanity. That’s all we can do. I’m a grain of sand, but I’m still here. That’s the hope.

CJ: We’re all grateful. Thank you so much.

DR: I pay my respects to the readers and members and supporters of Project Ploughshares. I’m a supporter myself, reflecting my hope in your work and my deep respect for you and your predecessors, not least, Ernie Regehr and Murray Thomson for having the vision to start Project Ploughshares. I encourage the churches that provide basic support to maintain that support, because you are having an effect on the people who think.

Cesar Jaramillo (Edited by Windy Stocker)