Main Feature

Key Note Speaker Buys into Inexact Mythology of De Roo

Patrick Jamieson, Victoria

Volume 39 Issue 1,2,&3 | Posted: April 5, 2024

While the event was an overall success with 120 people attending, the keynote address was originally supposed to be made by Vatican official Canadian Cardinal Michael Czerny, a friend and associate of Bishop De Roo. He had to bow out, and was replaced by Michael Higgins, an amusing speaker but quite a comedown. His focus seemed just slightly off.

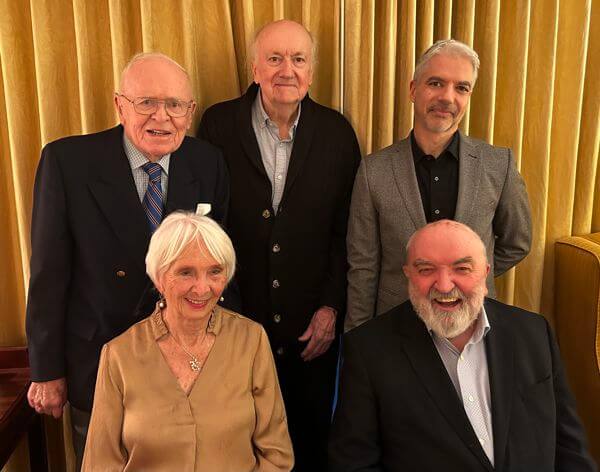

The evening before, I met Higgins at a cocktail party in the rooms of Douglas Roche, a fellow member of the planning committee. Higgins and I had originally met in 1977 but he did not remember. He had been replaced as president at St. Thomas University in Fredericton by my roommates’ wife Dawn Russell, which I wanted to mention to him. I also had a couple of tester questions just to get a sense of his acumen.

He announced at the party that he was obviously not a confidante of Bishop De Roo, so would be taking a Canadian church politics perspective in his speech; looking at De Roo in the context of the church politics of the episcopacy. This sounded like trouble on some level but I wasn’t prepared for the tone of his talk.

After the first ten minutes I had spotted about the same number of inexactitudes from the work I had done on my three books on De Roo; the kind that come from cherry picking among the news headlines. Once a person met Bishop De Roo, all of the caricature writing about ‘Remi the Red’ immediately falls away but Higgins seemed to be buying a lot of it.

He was told at the last minute he would have 40 minutes rather than an hour, so had to cut from a lengthy section on the Mother Mary Cecelia legacy. It was just as well as Higgins gave a lot more significance to that strange episode than De Roo himself did. Much of the rest sounded more like a tribute to Cardinal Carter of Toronto with only an occasional reference to someone named Remi De Roo. Carter was not an illuminating figure in terms of De Roo. As a result, it felt like a lot of damning with faint praise.

My feeling was that the speech did a disservice to De Roo’s whole purpose. But few in the audience seemed to mind due to his eloquence and amusing style of speech.

Except for one senior seriously distressed organizer to whom Higgins was seen as something of a show-off, cherry picking his moments and his issues and giving the whole treatment as an amusing performance. On many levels, for me, the whole talk was a waste of time except as a digestive after dinner talk or the first draft for a magazine article in a liberal secular magazine like Atlantic or Harper’s in their heyday.

As a journalist I could be bemused as easily as the audience, having grown almost philosophically used to such treatment of De Roo, and I might have been tempted to let it all go but as I say, one of the key organizers found the whole thing extremely distressing who did not want Higgins’s name suggested as an official biographer for De Roo. Finding a biographer was one of the hopes for the symposium, that someone might surface.

At some point I started to recall reading books by Higgins decades before and remembered the reason why I quit reading him until he started having opinion pieces in the Globe and Mail since Francis became pope.

His article in a book of profiles on prominent Catholics about Bishop De Roo, and his book on Thomas Merton both had odd off-putting takes on both figures. One of my tester questions had been about the new books on Merton’s murder by the CIA. He dismissed that off hand which told me all I needed to know. One of the recent volumes by Turley and Martin had a section about Higgins’s attitude so I shouldn’t have been disappointed. It underlined the inevitable difference between progressives and prophetic Catholics.

Higgins and Donald Grayston, an Anglican priest, interviewed me in 1977 for the job of arts festival organizer at a Thomas Merton Symposium at Vancouver School of Theology where I was working on my masters of divinity degree. Children were coming along so I ended up moving to Ottawa for a job and never did attend the Merton events. Higgins and the now departed Grayston were leaders in the Thomas Merton Society which has resisted the idea that Merton was important enough to be assassinated but two recent volumes have been promoted by ICN that pretty well prove the opposite. He obviously had not read them with due diligence, as they say.

Higgins’s take of De Roo was that of a progressive liberal about a prophetic radical. De Roo was never concerned about skating on the surface. He always could be relied upon to go to the root of the matter.

So it is ironic and interesting that a key note speaker on Bishop De Roo would be, could be someone who bought into the conventional faux wisdom and mythology about the bishop; probably the most misunderstood prelate in Canadian history due to liberal media prejudice and professional jealousy by more senior hierarchy. As Doug Roche says in his report on the symposium, (see Lead Story) “De Roo cannot be measured in political terms as if he were just another ecclesiastic who outshone his peers. Some now seek to marginalize De Roo as but a loose cannon in the august Church of Rome.” Higgins had no problem repeating key elements of the false image, largely from the perspective of ecclesiastical gossip and eastern Canadian perspective.

The best example was the distortion that seeped into the media reporting on the financial issues after De Roo retired. The contrast between the local Victoria reporting and the Globe and Mail which actually looked at the court record and vindicated De Roo.

Having written a book on the saga, and documented in my journalistic biography the way that Catholic prelates were treated who strayed too close to the fire on the left, it was rather shocking how superficial Higgins’s research was. One tries to be open and tolerant in such circumstances but my senior colleagues’ distress underlined how seriously it was being received.

His first memory of De Roo was the Mother Cecelia legend which tied in with the post retirement scandal of debt due to a loan to a horse farmer and the purchase of land in Lacey Washington to offset the two million dollar debt.

De Roo’s true nature as a prophet of the Canadian church was only casually mentioned. Higgins seemed more impressed with liberal reformers like Cardinal Carter rather than radical structural critics like De Roo.

2.

As someone who had been intensely studying Remi De Roo and his unique career, and life, for five decades, I had an unfair advantage over someone who had thirty days to put together a keynote address before a hundred rabid Remi fans. And I had to respect the organizers who picked him. But it is like any experience, once you have had it, reflection reveals strength and weaknesses to the exercise.

For all his clever turns of phrase, there did not seem to be any major redemptive moment. He had tried to be objective, but we are still too close to the heat of the battles De Roo found himself enveloped within to allow real historical objectivity, such as we are hoping for in the way of an authorized biography.

As I mentioned in one panel session at the symposium, I have a sense my biography of the bishop, In the Avant Garde, The Prophetic Catholicism of Remi De Roo, although written in an objective journalistic manner, will be seen as contemporary hagiography when a major serious historical biography is done. Certainly there is enough written about him to warrant such a book, and he was controversial enough, despite his honest disclaimers of eschewing controversy.

Professional jealousy aside, De Roo’s giftedness, as Laurier Lapierre stated in his introduction and post TV interview reflection in 1983, was something extraordinary. There he astutely avoided being drawn into petty quarrelling with his fellow bishops and issue opponents. De Roo always expressed admiration and respect for his controversy opponents.

I could imagine him being bemused by Higgins’ assertions of contentions for facts. Higgins did not seem capable of rising above the more inflammatory occasions, such as Mother Cecilia and Cardinal Carter and who should take credit for the cleverness of the solution of the Winnipeg statement on the birth control controversy of Humanae Vitae in 1968.

It was not Cardinal Carter that the extreme right of the Canadian Church castigated for that clever development. But it was Carter who according to Higgins took credit for its astuteness, when it was obvious Carter did not have the language skills or mental attitude to achieve the relative peace with the theologians that threatened to tear apart the American Catholic Church where the bishops and the periti butted heads over the same issue.

De Roo’s modesty about his abilities and his almost countervailing image were what one immediately took away from close encounters. I recall my mother telling of her first encounter at St. Andrew’s cathedral. Margaret Harris, as a St. Ann’s Academy graduate, was used to pomp and circumstances of pre-Vatican II Catholic liturgy and ceremony.

She said the altar servers were all gathered in the vestibule waiting for the bishop to arrive with some noteworthy ceremony when she suddenly realized he had been there a while almost invisible yet his reputation preceded him in their expectation. I could tell she was refreshingly surprised when he just got on with business, something she always admired. Margaret was my family touchstone for what was normative within Catholic culture.

That and a few similar episodes told me of her approval with changes in the church including her approval of women’s ordination, but then she did have a daughter who was a solid post-Vatican II moral theologian.

3.

Higgins talk was followed by two panels of four speakers each and then a book launch of De Roo’s words from speeches and writings, edited by his close associates Pearl Gervais and Douglas Roche (see Lead Article).

The panels were on social justice and Remi the Person, and they served to ground the rather abstract nature of Higgins’ speculations. (See articles by Christine Jamieson, Sue Rambow and Dave Szollosy elsewhere in this edition).

We probably made a mistake in choosing him as the keynote but it did not really impact the overall effect of the celebratory event. Between the three main planners of the symposium, they had produced ten books with and on De Roo. It could have been interesting to cobble together a keynote from those three of twenty minutes each. Perhaps next time. Meantime Michael Higgins had served his purpose to stimulate focus and discussion of the truth of De Roo’s life and work.

In the final analysis, it is Higgins’s soft focus as a liberal progressive trying to examine a radical prophetic figure that lets him down. With De Roo and another subject of Higgins’s focus, Thomas Merton, one needs a sharper focus on his salient characteristics to catch the power of the person.

Merton and De Roo were scheduled to meet in late 1968 when Merton embarked on his fateful trip to Asia. One would think Higgins would have been all over that aspect of the De Roo story but it is evidence that he didn’t consult my book In The Avante Garde in his preparation for the talk.

Coincidentally a further chapter of the Merton murder saga is being featured in this edition of ICN (see article in the Other News tab), a saga that Higgins told me was all hogwash. As with Merton, Higgins’ focus on De Roo perhaps misses the salient feature of the man due to his preferred narrow focus, rather than see what is actually there.

Patrick Jamieson, Victoria