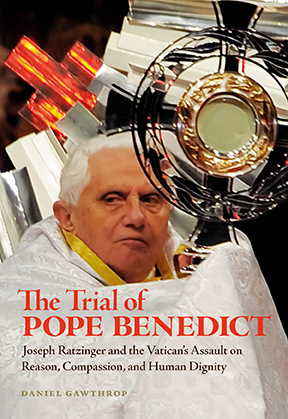

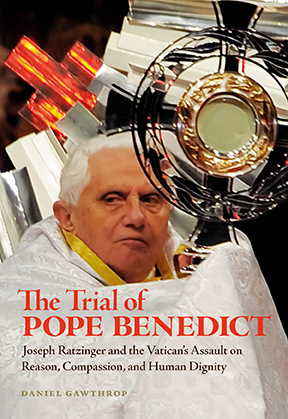

BOOKS: The Trial of Pope Benedict by Daniel Gawthrop

Volume 27 Issue 4, 5 & 6 | Posted: May 27, 2013

New book on the Papacy and Vatican to publish on June 25, 2013

P-ISBN: 978-1-55152-527-3

$15.95 list – 304 pages

Publisher – Arsenal Pulp Press

www.arsenalia.com

INTRODUCTION

New book on the Papacy and Vatican to publish on June 25, 2013

P-ISBN: 978-1-55152-527-3

$15.95 list – 304 pages

Publisher – Arsenal Pulp Press

www.arsenalia.com

INTRODUCTION

On February 28, 2013, Benedict XVI became the first pope in nearly six hundred years to resign. He abandoned a role that nearly every one of his predecessors had seen as a calling from God to be heeded until the moment of death. Joseph Ratzinger, the man who became Benedict XVI, also relinquished a controversial religious career in which he was largely responsible for the Catholic Church’s prodigious troubles.

In “The Trial of Pope Benedict,” Daniel Gawthrop persuasively argues that Ratzinger must not be allowed diplomatic immunity from the abuse scandals that have rocked the Vatican. Gawthrop not only accuses Ratzinger of quitting to avoid dealing with an explosive new sex scandal, but also indicts him for promoting a toxic theology whose destructive impact can be felt far beyond the Church itself. As proof, the book examines Ratziner’s career in all its infamy, from his medieval understanding of women and demonization of homosexuality to his war on liberation theology.

Gawthrop also offers insight into newly elected Pope Francis I (Jorge Mario Bergoglio) and provocative ideas on how the Church can transform itself as a means to restore the faith of its disenchanted followers.

EXCERPTS

At Vatican II

At thirty-five years of age, Ratzinger was one of the youngest theological experts invited to Vatican II when he accompanied Cardinal Frings as an advisor. A member of the Central Preparatory Commission for the Council, Frings was sent drafts of texts (schemata) that were to be presented to the conciliary fathers for their discussion and vote after the assembly had convened. He sent Ratzinger the texts for criticism and suggestions for improvement.

Although the documents gave the young Ratzinger “an impression of rigidity and of insufficient openness, of an excessive link with neo-Scholastic theology, of thinking too much professorial and too little pastoral,” as he would put it in Milestones, Ratzinger found no grounds for “radical rejection” of what was being proposed. On the contrary: when he arrived at Vatican II he was still seen as a leading figure in the liberal wing of the German church – an impression only reinforced by the events of November 8, 1963.

On that morning, Cardinal Frings delivered a blistering attack on Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, the leading conservative voice at Vatican II and prefect of the Holy Office of the Roman Curia (otherwise known as the Inquisition, later renamed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith). The strategy behind this assault – which painted the Inquisition and Cardinal Ottaviani as unjust, undemocratic, and authoritarian – was to pre-empt any move by the curial cardinals to rubber stamp the Vatican II documents before a full discussion of them had taken place.

“The Holy Office does not fit the needs of our time. It does great harm to the faithful and is the cause of scandal throughout the world,” said Frings, speaking words written by Ratzinger. And then this: “No one should be judged and condemned without being heard, without knowing what he is accused of, and without having the opportunity to amend what he can reasonably be reproached with.”

The conciliary fathers erupted into applause several times during Frings’ address. If only they knew who had written these lambasting words, and what would become of him. If only they knew that, eighteen years later, Joseph Ratzinger would have Ottaviani’s job and be accused of much the same things; that his passionate call for due process in 1963 would be abandoned, all those years later, in favor of a punitive approach that would make Ottaviani’s modus operandi seem quaint by comparison.

There were two principal tracks for discussion at Vatican II, as Ratzinger put it in his memoirs: “the interior life of the Church” and “the Church vis-à-vis the world.” As far as the former was concerned, reform of the liturgy was the main issue – although this was not exactly controversial among the conciliary Fathers.

Cardinal Montini (who, as Pope Paul VI, would take over the presidency of Vatican II after the death of Pope John XXIII on June 3, 1963) saw liturgical change as one of the less substantial tasks on the agenda. In Ratzinger’s view, the real drama began when The Sources of Revelation (on scripture and tradition) was presented for discussion. The problem, he recalled later, was that the “historical-critical method” of Biblical interpretation favored by liberals had become the dominant Catholic theology in the climate of the Council.

“By its very nature, this method has no patience with any restrictions imposed by an authoritative Magisterium,” Ratzinger recalled in Milestones. “In other words, believing now amounted to having opinions and was in need of continual revision.”

Of course, real liberals, such as the German Jesuit Karl Rahner, saw things differently. Where Ratzinger spoke of “revelation” and the “authoritative Magisterium,” Rahner's thought was sprinkled with words like “grace,” “mystery,” and God as a “possibility” that was up to the beholder to see.

Rahner’s theology was based on the idea that all human beings have a latent awareness of God in any experience of limitation in knowledge or freedom as finite subjects; such experience he described as “categorical” in the Kantian sense, because it was the “condition of possibility” for such knowledge and freedom. Given their subsequent differences, it is noteworthy that, at Vatican II, Ratzinger and Rahner collaborated on a schema about revelation for Cardinal Frings.

According to Ratzinger, the second, “more developed” version that the two men produced was more Rahner’s work than his. The collaborative experience revealed that the two theologians “lived on two different theological planets”: Ratzinger was from the Munich School of Scriptural Literalists; Rahner was from the Heidegger School of Reasonable Doubt. Or so the former implied in his memoirs.

“[Rahner’s] was a speculative and philosophical theology in which Scripture and the Fathers in the end did not play an important role and in which the historical dimension was really of little significance,” wrote Ratzinger. “For my part, my whole intellectual formation had been shaped by Scripture and the Fathers and profoundly historical thinking.”

It was during this period between the summer of 1963, when Ratzinger was approached by the University of Munster and invited by dogma specialist Hermann Volk to take his chair, and the Bamberg Conference of 1966, when he sounded the first warning bells about “false renewal” that Ratzinger’s position hardened into conservatism, and he began to see Vatican II more as a destructive force for the church than a positive one.

“The impression grew steadily that nothing was now stable in the Church, that everything was open to revision,” he would later write. Vatican II was like a great church parliament that could “shape everything according to its own desires.” The faith, he added, “no longer seemed exempt from human decision-making but rather was now apparently determined by it.”

It was in this vein that a kind of elitism began to take hold in Ratzinger, fueled by fear of the times he was living in. He was not excluding himself when he penned the following: “The role that the theologians had assumed at the Council was creating ever more clearly a new confidence among scholars, who now understood themselves to be the truly knowledgeable experts in the faith and therefore no longer subordinate to the shepherds.”

By “the shepherds,” Ratzinger was referring here to the bishops. In his view, the bishops – along with parish level priests – had been fiddling with the faith by advancing all manner of touchy-feely nonsense in their post-conciliary ministry.

What really made his blood boil about Vatican II was “the idea of an ecclesial sovereignty of the people in which the people itself [sic] determines what it wants to understand by Church, since 'Church' already seemed very clearly defined as ‘People of God.’ The idea of 'The Church from Below,' the 'Church of the People,' which then became the goal of reform particularly in the context of liberation theology, was thus heralded.”

Liberation Theology

More than a quarter century after his official “instruction” on liberation theology, one finds at least two tragic ironies in Ratzinger’s successful efforts to stamp out this popular grassroots movement. The first is the brilliance with which he conflated the evils of Stalinism in Eastern Europe with the pedagogy of the oppressed in Latin America.

In so doing, he adopted the red-baiting logic of Ronald Reagan to reject the concept of “social sin” in a part of the world whose socio-cultural and historical realities bore little resemblance to those of the continent on whose Marxist example he relied to build his case. The second irony is how, in “correcting” a pope who did not completely share his views on liberation theology, he blinded John Paul II to the church’s double standard with regard to “people power.” In Wojtyla’s native Poland, the church sided with the workers, thus allowing priests and bishops to help overthrow a Communist dictatorship. But in Latin America, the church sided with the state military and the corporations, thus rendering clerics impotent and exacerbating poverty. Thanks to the church’s support of right-wing dictatorships or their elected, corporatist equivalents, hundreds of thousands of human lives were sacrificed on the altar of religious orthodoxy that Ratzinger and, to a lesser extent, John Paul II espoused.

What was Ratzinger’s problem with liberation theology? What was wrong with bishops, priests, and theologians joining with civil society to improve the plight of the poor and challenge the political oligarchies responsible for their oppression? Was it not the church’s duty to defend the world's disadvantaged and work to secure their redemption? Well, no, according to the CDF prefect, it wasn’t. First, a liberation theology based on Marxism only replaced the Christian promise of redemption through Jesus with a “messianism” based on materialism; it substituted a reward in paradise with revolution. This was wrong, said Ratzinger: the only redemption possible was individual salvation through Christ. Second, liberation theology challenged the internal hierarchy of the church by aligning priests with the poor and allowing earthly political realities, not Rome, to drive the pastoral agenda.

****

Liberation theology was inspired by Vatican II ecclesiology. Gaudium et Spes instructed the church to “take on flesh” by joining with social movements to build a society that reflects human dignity. In 1968, an assembly of Latin American bishops in Medellin, Colombia, endorsed a “preferential option for the poor,” an imperative for the church to align itself with the underprivileged against powerful elements defending the status quo. Throughout the ages, the church had perpetuated feudalism in Latin America – from the missionaries who evangelized for the European conquerors to contemporary church leaders who always sided with the elites. Now its leaders were prepared to switch loyalties and, by supporting the poor, do “what Christ would do.”

One of liberation theology’s earliest proponents was Gustavo Gutierrez, a Dominican priest who served as theological advisor at the Medellin conference. His book, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics and Salvation (1971), became the movement’s seminal text. In it, Gutierrez spoke of liberation theology as an indigenous movement particular to local conditions in the nations where it arose.

But Ratzinger saw it as an ideological import from Europe, leftist pablum that was being force-fed to the ignorant masses by intellectuals who had “read too much German theology.” The movement's practitioners frequently quoted Johann Baptist Metz of Munich, the founder of “political theology,” and Jurgen Moltmann of Tubingen, founder of the “theology of hope.”

Metz saw Vatican II as a clarion call for Christians to read the “signs of the times” in social and political movements, to align themselves with those seeking to improve the human condition. Moltmann was a Lutheran who embraced a more radical vision of Christ as fearless rebel for social transformation.

Ratzinger also noted that liberation theology's most influential figures had studied in Germany or elsewhere in Europe: Gutierrez at Louvains, Lyons, and Rome; Brazilian Franciscan Leonardo Boff at the University of Munich; and Uruguayan Jesuit Juan Luis Segundo at the University of Paris.

Notwithstanding the European training camp for its intellectual standard bearers, the ideas behind liberation theology were not imported. They were the product of indigenous popular movements tied to pastoral work in Latin America and inspired by experiences of the local poor.

To begin with, there were the “base communities”: small groups (usually ten to thirty people) of poor Christians who met to discuss social issues in the context of the Bible. Throughout Latin America there were said to be tens, possibly hundreds, of thousands of these small groups. Sometimes they met under the guidance of a priest, but usually they were lay-led.

The scriptural study and reflection was goal-oriented: it was supposed to lead to action. Liberation theologians aligned themselves with base communities rather than with the institutional church, its hierarchy or its upper class supporters. In progressive dioceses, being part of a base community was a critical part of doing one’s job as a priest.

Another liberation theology concept native to Latin America was “social sin,” which expanded the concept of sin from the individualistic (i.e., personal transgressions such as lying and stealing) to the collective (i.e., institutional corruption, police violence, neocolonialism). The forgiveness of sin by Jesus Christ thus involved far more than the redemption of individual souls; it also meant transforming unjust social realities. This was crucial to liberation theology’s core belief in what it meant to be a good Catholic.

What kinds of actions did this involve? Everything from eucharistic strikes (withholding the sacraments from politicians, village headmen, or army officials who had “sinned” against the people) to revolutionary violence (only as a last resort when all other means to social justice had failed). The church had always enabled social violence by condoning the status quo; it had enabled state violence by turning a blind eye to military repression. So how could it condemn the desperate violence of the poor who needed food, housing, and jobs?

The problem, as Ratzinger saw it, was ideology. While liberation theologians saw the historical Jesus as champion of the marginalized, the CDF prefect saw only Che Guevara and the Baader-Meinhoff gang. In his view, a theology based on Marxism could only lead to terrorism. Who could trust it, after all, if even the Medellin conference of bishops with its “pastoral reflection on poverty,” as Gutierrez put it was unwilling to renounce violence?

The problem, as Ratzinger saw it, was ideology. While liberation theologians saw the historical Jesus as champion of the marginalized, the CDF prefect saw only Che Guevara and the Baader-Meinhoff gang. In his view, a theology based on Marxism could only lead to terrorism. Who could trust it, after all, if even the Medellin conference of bishops with its “pastoral reflection on poverty,” as Gutierrez put it was unwilling to renounce violence?

Priests such as Father Camilo Torres, a Colombian leftist killed in 1966, had, in fact, taken up arms, joined guerrilla movements, been killed, and then celebrated as martyrs. Liberation theology by definition supported leftist political movements, some of which were proudly Marxist and a few of which advocated violence in building a just society.

Ratzinger also thought that liberation theologians relativized Christian doctrine through orthopraxis, the privileging of “correct action” before “correct belief.”

Daniel Gawthrop is the author of four books, including “The Rice Queen Diaries” (Arsenal Pulp Press), “Affirmation: The AIDS Odyssey of Dr. Peter” and “Vanishing Halo: Saving the Boreal Forest”. He spent sixteen years as a journalist and editor for a variety of publications. Gawthrop’s writing has always focused on contemporary socio-political issues through a progressive lens.