Thomas Merton’s Unspeakable End

Patrick Jamieson, Victoria (A Book Review Essay)

Volume 27 Issue 1, 2 & 3 | Posted: March 7, 2013

Thomas Merton: Monk on the Edge Essays edited by Ross Labrie and Angus Stuart, Thomas Merton Society of Canada, 2012, 199 pages ppbk

Thomas Merton: Monk on the Edge Essays edited by Ross Labrie and Angus Stuart, Thomas Merton Society of Canada, 2012, 199 pages ppbk

Before I get into what I have to say, let me first declare how this is an excellent book of ten essays by Canadian Merton scholars as diverse as a university president, to a prize-winning poet, to an Anglican priest with a special interest in Beatnik culture (and Thomas Merton’s relationship to it).

Before I get into what I have to say, let me first declare how this is an excellent book of ten essays by Canadian Merton scholars as diverse as a university president, to a prize-winning poet, to an Anglican priest with a special interest in Beatnik culture (and Thomas Merton’s relationship to it).

Merton, if he needs any introduction, was a Trappist Monk who led a full and worldly life, to quote the promotional blurb of his runaway bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1947. Merton entered the monastery at age 27 and died after 27 years to the day, under curious circumstances, to say the least.

Merton was indeed a monk on the edge, the cutting edge of a multitude of cultural and ecclesiastical (and political) movements in his time. This book, if nothing else will convince you of his extreme and competent diversity. He had an insatiable spiritual curiosity.

More importantly, Thomas Merton may be dead but he won’t lie down, as my mother used to say. Like Tielhard de Chardin, his influence today may be stronger than when he was alive, and it was very strong back then. Merton evolved into the most influential political spiritual writer of his time in North America.

Even more so today, his time has come. A seriously prophetic figure, signs are he was probably murdered. A political assassination. All the facts are not in, or at least visible.

Certainly he died rather mysteriously in 1968 when away from his monastery attending a religion and Marxism conference in Bangkok. His body was flown back to the United States in an air force bomber despite his radical pacifism. Merton’s prophetic nature as a symbolic figure explains some of his enduring appeal.

2

I have been reading Merton since I was about twelve years old when my older brother, in an effort one Friday evening to dissuade me from hanging around with him and his teenage pals, threw on my bed a copy of The Sign Of Jonas, Merton’s monastic journal. It was effective bait. I became transfixed by his writing, its style, his voice and his distinctive yet familiar personality. And of course, his subject matter, religious identity.

At University I was forever giving copies of The Seven Storey Mountain to my atheistic pals who would admit the story was pretty good if you skipped the religious parts. Friday evening party discussions inevitably gave way to me ranting about Merton and Tielhard as people moved to other rooms in inebriated avoidance.

A highlight from the 1960s in Vancouver was going into my favorite Granville Street Bookstore in the summer of 1968 and following the enthusiastic clerk to the aisle to show me Merton’s newest book Raids on The Unspeakable, his favorite book he confided in its preface. Raids said it all, the summer before his death.

It read like beautiful literature, with topical, pungent prose that introduced his final phase of mature writing. ‘The Unspeakable’ became his enigmatic phrase which subsequently took on an ominous postmortem hue.

When this 2012 book of essays came out with its captivating titles Prophecy and Contemplation by Michael Higgins, Merton’s Mystical Visions by poet Susan McCaslin, Merton and The Beats by Angus Stuart, Merton on Atheism in Camus by Ross Labrie, I wanted to get into it while looking for any hint of a certain subject Was he assassinated by the CIA? Was Merton an overlooked ‘60s assassination? Some serious people thought so.

3

Skip ahead to the mid 1990s to a Catholic Press Conference in a Vancouver hotel meeting room. I had left the Island Catholic News a few years before in the capable hands of editor Marnie Butler, also a close friend. Marnie was a convert to Catholicism in the late 1980s and the ICN Board recognized in her the gifts and ability to run the paper.

Butler was what I termed the last Catholic convert from the left, drawn into the church by Bishop Remi De Roo’s social justice charism of prophetic Catholicism.

The meeting was the Annual General Meeting of the Catholic Press Association of Canada, a small gathering of 20-30 including clerics, a bishop or two and all the mostly male editors of the half dozen Catholic newspapers across Canada. I had worked for a number of them. The topic turned to Merton and the tragic loss of his privileged sensibility and disappearance of a writer approaching his peak at age 54.

In her assured yet off-hand manner, Marnie simply announced that he had been assassinated. This stopped the conversation in its tracks. I looked around at their faces, wondering what their reaction would be. One of the mild-mannered clerics muttered that he had never heard that idea before.

At the time of Merton’s death, electrocuted after a bath in his hotel room between sessions at the conference in Bangkok on December 8, 1968, Marnie was part of a circle of peace studies and activism surrounding folksinger Joan Baez who had instituted the Centre for the Study of Non-Violence in Palo Alto, California. Baez had grown up a Quaker fully embracing its radical peace tradition. She had also visited Merton at Gethsemane and only half-jokingly suggested they run off together and leave it all behind; such was his impact on the Queen of folk music at the time; and his attraction and hold on the youth of the radical left in America.

In those circles it was immediately assumed he was killed for his influence on the radical Catholic Left. For a number of years he led a retreat at Gethsemane for Dan and Phil Berrigan and leaders of Dorothy Day’s Pacifist Catholic Worker movement. His influence was extensive and spreading in the face of the Vietnam War resistance. The escalation of the leftward swing of the Roman Catholic Church was extremely alarming for the powers that be of the time.

The direct murder of Archbishop Romero and the Salvador Jesuits was the result of just one wing of American State action against this insurgency of transformative Catholic social teaching which continues to this day. The retirement and replacement of the present pope Benedict XVI is a key moment in this process.

Marnie Butler brought this perspective to the dialogue on Thomas Merton as martyr. Her remarkable contribution to the Catholic social journalistic tradition was precisely this courage and clarity rooted in her almost uncanny intuitive ability. It is an ability I have come to rely upon in my own spiritual discernment process in my life and work.

In the early 1990s I had made a personal study of the assassination of JFK, another famous Catholic. One of the most significant aspects of the cover up in the Kennedy murder was the way that inconvenient witnesses die conveniently to the conventional wisdom around the JFK killing.

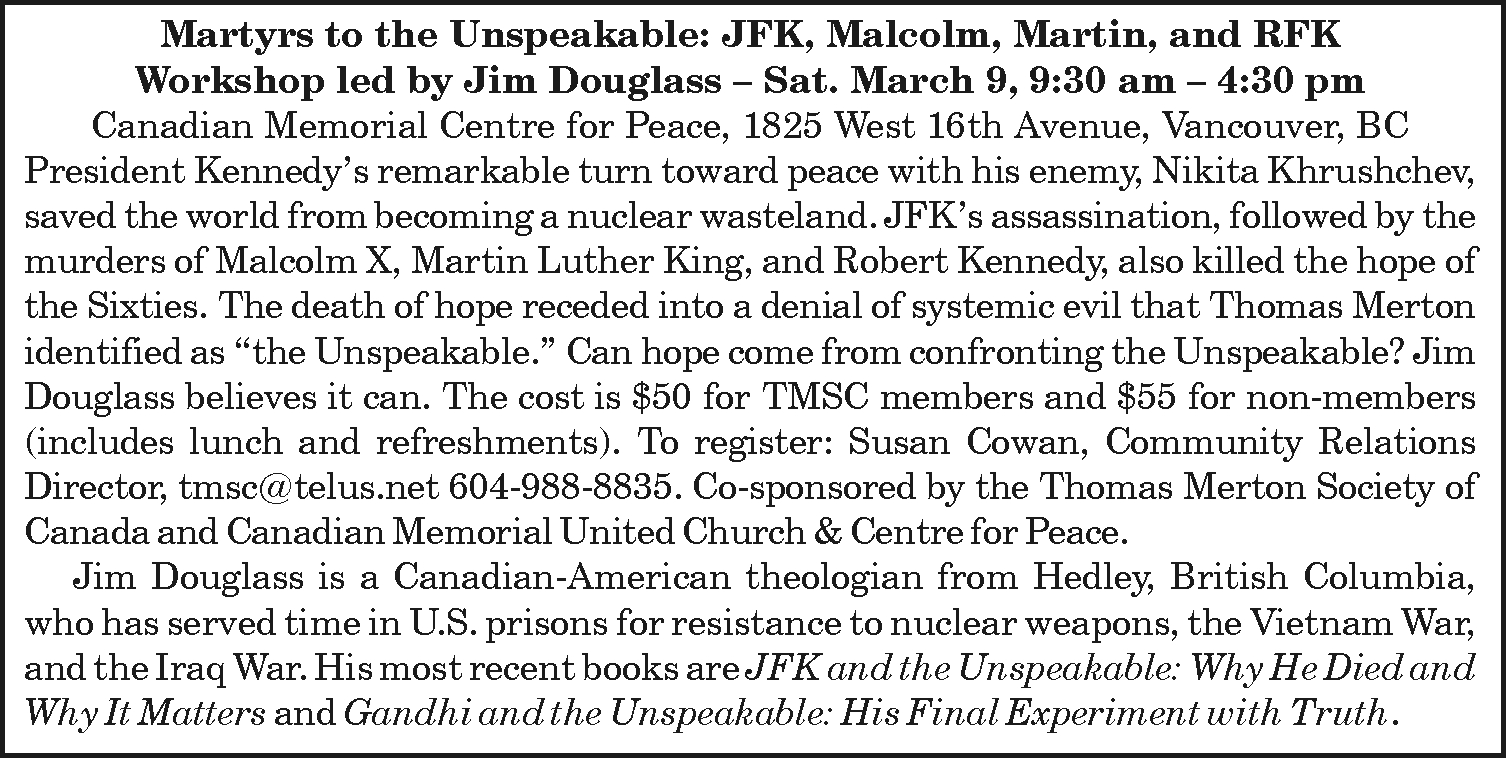

The ‘accidental’ ways that the CIA had of eliminating people I found particularly fascinating and applicable to Merton’s strange accidental death. ‘The Unspeakable’ continues to be an absorbing theme in the process of Catholic social justice teaching. March 7, 8 & 9, the Thomas Merton Society is sponsoring activist and author Jim Douglass to speak in Vancouver on ‘The Unspeakable’ aspect of current political culture. See http://www.merton.ca/

Patrick Jamieson, Victoria (A Book Review Essay)