Thomas Merton Crime Scene Photos

Hugh Turley & David Martin, Hyattsville, MD

Volume 39 Issue 1,2,&3 | Posted: April 5, 2024

INTRODUCTION

The photographs of Thomas Merton’s body taken by the first witnesses were deliberately hidden for almost 50 years. Our discovery of these photographs has been ignored as if they were never found.

David Martin and I have written a careful analysis of why the photographs were taken, why they were kept secret, and why they continue to be suppressed.

The abbot at Gethsemani refused to grant us permission to publish drawings of the photographs in our books. My understanding is that a newspaper, like ICN, may be able to publish these images under the “fair use doctrine” and the public right to know.

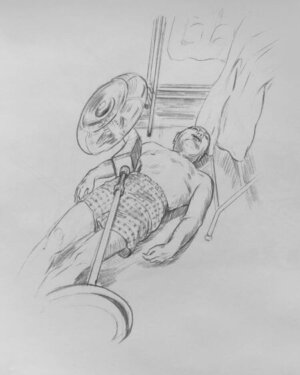

I am not including the actual photographs but only drawings that I paid an artist to produce for me. I was told that because the images are of photos owned by the Abbey of Gethsemani I cannot publish the drawings without permission from the abbey.

On December 10, 1968, at around 4 pm at a cottage at the Red Cross retreat center near Bangkok, Thailand, where they were attending a Catholic monastic conference, three Benedictine monks found Thomas Merton’s body when they entered his room. Abbot Odo Haas, Archabbot Egbert Donovan, and Father Celestine Say immediately recognized that Merton was dead. The scene was so odd that they did not touch anything before they photographed the scene to preserve the evidence.

This photographic documentation of Merton’s body at the scene created a permanent record that preserved details of the body position, appearance, identity, and final movements. The monks intended to give the photographs to the Thai police to show them how they had found the body, but when the police arrived, it became clear to the monks that the police were not doing a proper investigation.

Fr. Say took two photographs of Merton’s body from different angles. He later said that he did not tell the police about the photos because he thought that they might confiscate his film and camera. After the film was developed, he sent one of the photographs (the other was underexposed) and a letter on March 18, 1969, to Merton’s Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky. Burning with curiosity over the odd death scene, Say asked Abbot Flavian Burns if there had been an autopsy to determine the cause of Merton’s death before his burial. The abbot, in fact, had not ordered an autopsy and none had been done, although the doctor’s certificate and the death certificate affirmed that a “post-mortem examination” had been done in accordance with the law.

Abbot Flavian shared Say’s photograph with John Howard Griffin, who had been named as Merton’s biographer. Griffin immediately recognized the significance of Say’s photographs and joined Abbot Flavian and Brother Patrick Hart in an effort to secure the film negatives from Say. They praised Say for taking the important pictures and asked him to send them the negatives so that they could be “protected.” Say sent his negatives to the abbot as a gift. The negatives became the property of the Abbey of Gethsemani.

Griffin advised Abbot Flavian and Brother Patrick that the negatives should never be published or available to anyone. What did the Benedictine monks see that prompted them to take photographs of Merton’s body? Why was it deemed necessary at the abbey that these photographs be hidden from the public?

The Associated Press reported on December 11 that Merton “was electrocuted Tuesday when he moved an electric fan and touched a short in the cord.” Their source was not the official Thai investigating authorities but rather anonymous “local Catholic sources.” The Gethsemani Abbey quickly echoed the AP conclusion and has adhered to it to the present day.

In 2017, we discovered Say’s negatives in the papers of John Howard Griffin at the Butler Library of Columbia University and quickly saw why they were hidden. With modern technology we were able to get the underexposed negative developed, and the two photographs reveal what looks for all the world like a crime scene that had been staged to appear to be an accident.

The first thing that the witnesses saw was the unnatural position of the body. They saw Merton lying flat on his back with his arms straight by his side. When someone falls on a floor, it is almost impossible that a person will fall straight back with their arms at his side. Normally knees bend and arms are extended out to break the fall. A falling person goes down akimbo and not straight.

One of the first witnesses wrote, “I can assure you that his arms were straight and lying at his side—a fact that somewhat puzzled me. I have been personally puzzled by the fact that his arms were in the position in which they were. It seems to me that if he was in any way touching the fan or had pulled it over on himself in falling, his hands hardly would have been in the position in which they were found.”

It appears that the last movements of Merton’s body were made by someone else, who placed his arms at his side to roll him onto his back. A fan was then placed on Merton’s body. The witnesses were confused by the stand fan lying across Merton’s body, resting on his right pelvis. The base of the fan was near his feet and the blades to the side of Merton’s right shoulder.

Vernon Geberth, author of Practical Homicide Investigation, writes that “if you have a gut feeling that something is wrong, then, guess what? Something is wrong.” The initial gut feeling of the first witnesses was their subconscious reaction to the presentation, which alerted them that things were not what they appeared to be. This was why Say took the photographs.

A perpetrator purposely alters the crime scene to mislead the authorities and/or redirect the investigation. Placing the fan on Merton’s body would have been a conscious criminal action on the part of the murderer to thwart an investigation. No wonder witnesses were bewildered.

The photographs are not the only indication of a staged scene. People die in one of four ways, natural cause, accident, homicide, or suicide. Geberth states that ambiguity is characteristic of a staged scene. Officially, Merton died of a natural cause. Contrary to the AP report, the Thai police, while deceptively noting the presence of the defective fan, had concluded that Merton had died of “heart failure” and that he was already dead before he encountered the fan. Hardly anything could be more ambiguous than a man happening to die naturally before encountering a household appliance manufactured by a reputable company (Hitachi) that just happened to be miswired and could provide a shock.

Some of the muddled descriptions of Merton’s death came from his former abbot, James Fox. Fox said that Merton had been electrocuted by a faulty wire in a large fan in his room. According to Fox, Merton either had a heart attack and grabbed the fan and it fell with him; or he grabbed the fan and it fell with him; or he had been fixing the fan and grabbed a badly insulated wire.”

The staged scene left the public to debate whether the cause of death was an accident or a natural cause. The placement of the fan by the perpetrator directed attention away from a head wound seen by witnesses. Authorized biographer Michael Mott in The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton revealed that the wound, which was in the back of Merton’s head, had “bled considerably.” In his very next sentence Mott writes, “The obvious solution appears to be that it was caused when his head struck the floor.”

Talk about ambiguity! Was it obvious, or did that appear to be the cause of the long-bleeding wound? Can anyone imagine a person falling backward onto a level floor receiving such a wound? It’s very doubtful that Geberth, a longtime homicide investigator for the New York City Police Department, would have seen anything obvious about it.

Say’s photographs were hidden for additional reasons. The photographs prove that Merton’s abbey knowingly spread false information. The abbey said the fan was found lying across Merton’s chest which had been burned deeply. A wound on the chest would suggest that it had something to do with the heart failure. Say’s pictures prove that there was no such burn on the chest. The abbey reported that there were cuts on Merton’s body and that he had taken a shower before his “accidental electrocution.” No cuts are visible in Say’s photographs and Merton was wearing his pajama shorts. He was not found near a shower and Merton would not wear pajamas in a shower.

If Merton’s death had been caused by “accidental electrocution,” then Say’s photographs would provide evidence. Say’s photographs did not support the false narrative, and they contradicted stories told by the abbey, which is the most likely reason why they were kept secret. The officials at the abbey also decided to keep hidden the official death certificate, the U.S. Embassy Report, and the Doctor’s Certificate of Death. None of those documents state that the cause of death was “accidental electrocution,” which would further explain the need for secrecy.

Standard police procedure is to treat every unattended death as a homicide until homicide can be ruled out. Nothing that the Thai police did was in keeping with that procedure. The apparently staged crime scene, the concealment of the official reports, the hiding of the photographs, and the invention of false stories are further indications that Merton was murdered.

Turley and Martin are the authors of The Martydom of Thomas Merton: An Investigation, (2017) and Thomas Merton’s Betrayers: The Case Against Abbot James Fox and author John Howard Griffin, (2023).

Hugh Turley & David Martin, Hyattsville, MD