The Existential Quest of Father David Bauer

Gary Mossman, Toronto

Volume 39 Issue 4, 5 & 6 | Posted: July 18, 2024

Father David Bauer (1924-1988) was ordained by the Roman Catholic Congregation of St. Basil on June 29, 1953, in Toronto, Canada. As with all Basilian priests, Bauer knew from the beginning that his life’s vocation was to be an educator. He could not have imagined that he would carry out that mission by devoting much of his life to Canada’s favourite sport: hockey; that he would gain national – and international – fame as the founder of Canada’s National Team Program and as a coach and manager of international hockey teams.

In the 1960s, Bauer became the face of Canadian amateur hockey, shepherded Canada’s teams at the Olympics and world championships, and reshaped Canada’s image as a sporting nation. His contributions to Canadian sport and society were recognized in 1967 when he was named one of the first recipients of the Order of Canada; in 1973, he was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame.

Bauer’s posthumous honours include induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame (1989), the Olympic Hall of Fame (1992) and the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) Hall of Fame (1997). If there was a hall of fame dedicated to priests in Canada, he would be enshrined there as well. Bauer’s most enduring contribution to Canada and the world; however, can be found in the deeply personal way he affected the lives of the people he met.

In spite of the fame and respect garnered by Bauer during his lifetime and the honours bestowed upon him after his death, little was written about how a Basilian priest came to be a world-renowned hockey coach, how that impacted the world of hockey, whether it resonated within the Catholic Church in Canada, and how Bauer’s unconventional career choices affected his standing within the Basilian community. Most significantly, there was no attempt to understand how those choices affected Bauer’s own appreciation of his role within the Congregation of St. Basil and the larger Catholic Church.

Finally, in 2017, Greg Oliver published: Father Bauer and the Great Experiment, a very good study of Bauer’s National Team Program, how it impacted the players who were involved and how the understanding of hockey in Canada changed because of Bauer. Oliver did well in laying out the building blocks of Bauer’s program. He explained how religion and Fr. Bauer’s family history was integral to the story, and elicited testimonies to the profound personal effect Bauer had on the players, as well as anyone else who was associated with the Program. However, an in-depth understanding of Bauer’s religious underpinnings and how he managed to incorporate a full time job in hockey into a life he had dedicated to teaching within the Congregation of St. Basil, was still to be written.

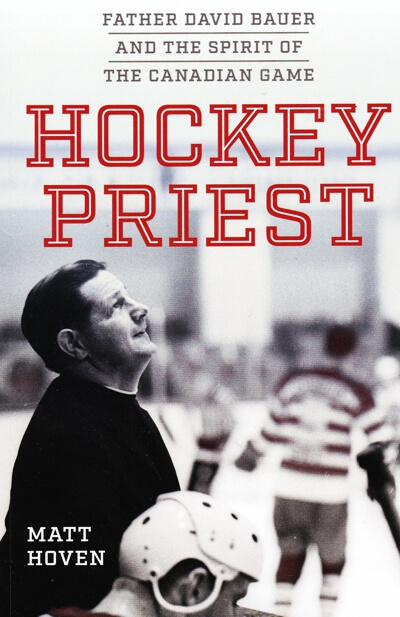

In 2024, a new book on Bauer has been published: Hockey Priest: Father David Bauer and the Spirit of the Canadian Game. The author, Dr. Matt Hoven, is an associate professor of sport and religion at St. Joseph’s College at the University of Alberta. As a graduate of Newman Theological College and a PhD in religion and education, the reader would expect to find a much deeper exploration of the role of religion and education in the personal life of Bauer, and how that affected his life decisions. Indeed, Dr. Hoven has done an admirable job in explaining how Bauer’s family history, the philosophical underpinnings of the Congregation of St. Basil, and the history of hockey in Canada, coalesced and came to life in his concept of a National Team Program. Dr. Hoven helps us understand how that program forever changed the way Canadians understand hockey. Dr. Hoven’s exhaustive research has also enabled him to make astute judgments and present a compelling picture of Bauer’s work with Hockey Canada (the governing body for hockey in Canada), as well as with the Japanese Hockey Federation in the 1970s and 1980s. The depth to which Bauer touched the lives of so many of the people he encountered during these years, as well as his legacy in Canadian hockey today, are also presented with deep appreciation and understanding. All in all, Dr. Hoven’s book increases our knowledge of the development of Canadian hockey over the years, and helps us understand how hockey in Canada might be different today if someone like Bauer was helping to oversee the sport.

Unfortunately, Dr. Hoven’s book is still a hockey book. It too misses an opportunity to understand the National Team Program as only one segment – albeit the most outwardly significant segment – in the life of a man whose entire being was dedicated to an existential search for the soul of his country and the meaning of his religious calling.

Bauer’s existential search began when he was growing up in Waterloo, Ontario. Now a mid-sized city ninety minutes west of Toronto that has been amalgamated with Kitchener, Waterloo had more of a small-town sensibility in the 1940s and 1950s. The importance of growing up in a large, close-knit, Catholic family with a strong sporting tradition is well established in Dr. Hoven’s book. As are the supreme athletic skills that earmarked David Bauer for a career in professional hockey, like his brother, Bobby Bauer who was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1996. Marriage and family life were also in the cards for David, until he abruptly changed course in 1946 and announced that he was entering the priesthood. On closer examination, however, it becomes clear that David’s decision was not sudden and did not signify a marked change of direction. Family members recalled how David always outlasted his siblings in the late-night discussions that their father, Edgar Bauer conducted on current events, religion and the problems besetting the world. Friends and family also recall that, when David was very young, he was already talking about world peace and what he might be able to do about it. David Bauer’s decision to become a priest was a natural evolution of an examined life of that era.

Attitudes were profoundly different for young Catholic men growing up in the 1940s than they were even two decades later. One of Bauer’s fellow Basilians who had gone to high school with David, explained to the author how he had seen his friend (David) become a novitiate (a first-year Basilian) in the spring of 1947 and decided that if he “did not have a girlfriend by the fall,” he too would join the Congregation of St. Basil. His story was not unusual for Catholic men prior to the 1960s and Vatican II. In contrast, Dr Hoven establishes that David Bauer entered the priesthood “with his head up.” Dr. Hoven, however, misses the opportunity to dig deeper into Bauer’s choice and its ramifications. While, in examining Bauer’s life, we do not sense that he ever seriously questioned his having entered the priesthood, it is of paramount importance to recognize that Bauer spent a lifetime questioning his ability to fulfil the demands that came with that choice, and that the questioning began even before he became a novitiate in 1947.

At the core of Bauer’s challenge to himself, and the challenge he would bring to so many relationships and teaching opportunities throughout his life, was something he learned from those long nights of discussion with his father. Edgar Bauer had impressed upon young David that: “one day you will have to answer to God for what you have been given.”

When David Bauer became a priest he expected that a life of teaching would become the basis for that answer. Sport, so important to the young David Bauer and his dreams of the future, was expected to take a back seat. The world of sport – specifically hockey – however, would not release him. As Dr. Hoven explains, Basilians believe in educating the whole person and, at that time, sport was an integral part of that education. Basilians also believe that it is God’s will that they accept whatever appointment is given them by their Order. Because Father Bauer’s first assignment was to St. Michael’s College, the Catholic high school in Toronto where he had excelled as a student athlete, teaching through sport became an essential aspect of the young cleric’s life. Furthermore, Bauer discovered that he was very good at it.

His students were enthralled by Bauer’s free-form discussions on philosophy and current events; they were mesmerized by his athletic skills and his ability to bring depth of meaning to his coaching. So many of those students only realized later in life that Bauer taught sport by teaching about life and taught about life by coaching sport. And even though the subject matter of Bauer’s teachings rarely strayed from the orthodox, his free-form teaching style encouraged his students to think freely. The cadre of former St. Michael’s students who later thanked Bauer for their ability to radically rethink their relationship with the Catholic Church, includes former Basilian priest, Paul Burns and world-renowned biologist, Leslie Kozak, as well as educator, activist and former editor of The Catholic New Times, Ted Schmidt.

Bauer coached the St Michael’s Majors to a Memorial Cup championship in 1961, defeating the best junior hockey teams from all across Canada. The following year, St Michael’s decided that the demands of Junior “A” hockey were threatening the educational standards of the school and withdrew their team from the Ontario Hockey Association. Although Bauer privately expressed his belief that accommodations could have been negotiated, he accepted the decision. Bauer also accepted the announcement, in June 1961, that his second Basilian assignment was to be the chaplain at St. Mark’s College on the Vancouver campus of the University of British Columbia, where hockey was barely an afterthought.

To Be Continued in Autumn Issue

Gary Mossman, Toronto