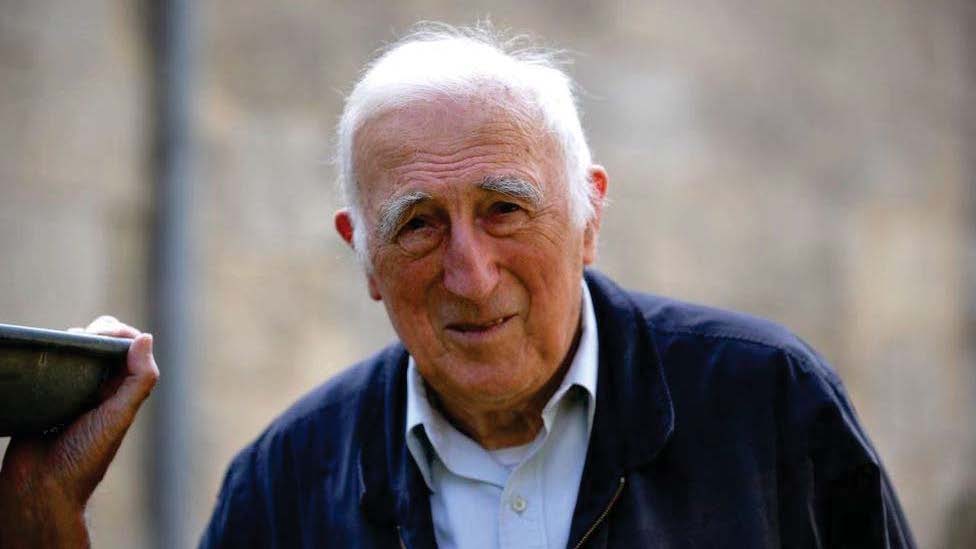

The Abjection of Jean Vanier – Investigative Reflection (Continued)

Walter Hughes, Ottawa

Volume 34 Issue 10, 11 & 12 | Posted: February 23, 2021

PART THREE

(for Part I, see ICN Summer 2020; for Part II, see ICN Autumn 2020)

A Breakdown of the L’Arche Report

2. FAILURE TO ACT IN OTHER SITUATIONS

so instead I started talking about the meaning of friendship and about sexuality. And all of a sudden the classroom wasn’t big enough to hold all the studentswho wanted to listen!

I have no information on how Vanier taught these topics. Given the date, I dare make a conjecture. In

December 1962, Playboy magazine-

While Jean Vanier did not know of

Père Thomas Philippe’s misbehaviour in the 1950s, he heard about the priest’s later misdeeds and failed to act. According to him, that was because he had not appreciated the seriousness of what happened. “A few years ago I was told of certain acts, but until now I remained totally in the dark as to the depth of their gravity.” Later, he apologized: “I ask the forgiveness of the victims for not having measured soon enough the extent of their traumatization and for not having been sufficiently sensitive to their suffering.” (my emphasis.)

These comments were in circular letters speaking to information that had come out in the 2014-15 inquiry into Père Thomas and so referred to the 1970-1993 period. About this, the Report says little, only:

The investigation heard allega- tions that Jean Vanier was aware of other situations of psychological or sexual abuse of L’Arche assistants by another person. Despite Jean Vanier’s denials when questioned by L’Arche International officials, his knowledge of at least some of the facts seems to be proven.

This comment may be referring to incidents reported by an association of parents. AVREF is a self-help group, created in 1998, of parents in France who feared for their children’s safety due to mental control by religious movements. From the outset, AVREF families worried about the Commu- nity of St. Jean, the monastery and convent set up by Father Marie- Dominique Philippe, brother to Père Thomas. (Cf. June 2020 ICN.) Online, AVREF publishes statements of victims of sexual abuse, including at L’Arche in Trosly. Three ex-assistants at Trosly alleged sexual abuse by Père Thomas. AVREF reported:

Numerous testimonies confirm the facts with which he (i.e. Thomas) is accused. Père Thomas was attracted to young women. Our interlocutor was 40 years younger than him. She is certain that his victims were numer- ous, over a period of decades, but that those who tried to speak – in particu- lar to Jean VANIER – were advised to remain silent about the abuses they hadsuffered. (My emphasis)

This statement supports the Report allegation that Jean knew about Père Thomas’ predatory behaviour as early as the 1970s, but not in the 1950s. Like many bishops in the Catholic Church at the time, Vanier heard credible allegations of sexual abuse but failed to report them to authorities. Vanier was not unusual. He stands out in these stories only because he is known as someone who listens to the vulnerable.

FALSE MYSTICISM

Mysticism is a form of understand- ing different from rational knowl- edge. Typically, it references a sense of unity with God or the meaning of our lives as part of a greater whole. Catholicism is full of mystical images. Pope Francis has been quoted as saying, “A religion without mysticism is a philosophy.” As a philosopher and theologian, Jean Vanier would naturally tend towards mystical language.

However, there is a more sinister meaning of mysticism – one which is totally modern and irreligious. That says that mysticism is claptrap – mere mumbo-jumbo meant to confuse the listener. This is how the Report talks about mysticism, intertwining it with ‘theories’ and ‘sexual practices’ in a nebulous fashion to suggest some- thing sinful on the part of Vanier.

The issue was that Père Thomas used religious talk to dominate a woman as he tried to bend her will to partake in sex. At least one of the two female informants who accused Père Thomas in 1951 was mature, edu- cated, and wise to him. In her state- ment, she said clearly and forcefully:

Then he began theories, to try to convince me, […]: the lost woman of Hosea, the sacrifice of Abraham, the glorious mysteries, the transcendence of the prophetic mission (of his mission) regarding the norms of morality. He asked me, most insis- tently, to bind myself to him by an act of absolute faith inthismissionandin himself. I replied that I could only make an act of faith in God alone, and trust in creatures only insofar as they were God’s instrument for me […]. He explained to me that it was not for me to make this discrimination, that he was an instrument of God, and therefore at present and directly moved by God […]. (p.8)

The Report says little about Vanier’s mysticism, his theories, or his sexual practices. What we read refers mostly to Père Thomas, and then indicates that those of Jean Vanier were ‘the same,’ ‘in line with,’ ‘similar to’ or ‘a series of indicators lead us to believe that….’ For proof that Vanier thought the same as Père Thomas, the Report offers two quotes (p.7) from Vanier:

It was obvious to him (Père Thomas) that I was his spiritual son who would do anything to support himinhisplans.

I am steeped in the thought and method of Père Thomas.

Both quotes are taken from interviews several years prior to the inquiry into Père Thomas. It is a gross quoting out of context to construe these words to say that Vanier approved of using religious language to seduce women. Vanier severely criticized his former mentor in 2016:

Through his repeated and repre- hensible acts, Père Thomas has shattered the trust that I had in him. I would like to add that there is abso- lutely no link whatsoever between the spirituality or the theology used by Père Thomas, which served to justify his abusive relationships with women, and the spirituality of L’Arche, as it was conceived, devel- oped and lived since its origins. (circular letter, October 2016)

The Playboy Philosophy

Jean Vanier’s education did not end with Père Thomas. He com- pleted a PhD in philosophy in 1962 from the Catholic University in Paris, where he completed his thesis on Aristotle, which became the basis of the first of his thirty published books. He was invited to St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto to teach ethics for the winter term in 1964. Jean wrote in a memoir of his letters:

This was the first time that I had ever taught. I was supposed to teach ethics, but I found that my students weren’t terribly interested in justice,

owner Hugh Hefner published the enormously influential book, The Playboy Philosophy. Professor Vanier would surely have had to respond to his students spouting lines directly from Hefner’s book, only a year old.

Hefner was gutting the moral sanctions against illicit sexual behaviour. While many debated whether Hefner went too far or not far enough, there was a subsequent relaxing of both legal and customary codes of sexual behaviour that rippled across the Western world. Sexual ethics were controversial and much written about in the third quarter of the 20th Century.

Established norms were collaps- ing. In the fourth quarter, many began to push back to say that such liberality had gone too far. During this period, decent people could disagree on how social norms should unfold.

Jean Vanier And Women – What The Report Says

The Report quotes some women as having some level of sexual activity with Vanier. One woman said, ‘I was in an inappropriate sexual relation- ship with Jean Vanier.’ In another case, ‘sexual touching’ is mentioned; in another, we did ‘everything except intercourse.’ There are other vague references to ‘love.’ The Report authors comment that ‘Jean Vanier

… crossed boundaries which are expected and necessary ….’ While the women are quoted as stating facts, the authors are making judgements that go beyond what the women said. This should be highlighted!

In making their statements, the women may have questioned Vanier’s ethics, but that is not the same as making allegations of assault. ‘Questioned’ is how the Report described the first woman’s comment about Vanier’ s behaviour. The authors are making judgements and calling them ‘findings’, while the victims are simply stating facts.

The authors provide no inferences between the women’s statements and the conclusions that they, the authors, drew. It is unfortunate that we do not have the personal stories of the women as they told the inquiry. It may well be that Vanier had a more relaxed personal attitude toward sexual relations than some of the women. Not everyone had the same boundaries.

In discussing sexual boundaries, the Report does not consider the fluidity of the 1970s and 80s. If we must judge, we need to establish what code was broken. Was it a house rule, a vow of celibacy, or a professional code of conduct? Was there a formal relationship between Vanier and the women which should have proscribed any sexual activity?

Allegations of sexual abuse against Vanier are what the media reported. The Report informs us that the team received six allegations from the alleged victims. One woman came forward in 2016 to question Jean Vanier s behavio’ur towards her in the 1970s. This is the only statement that Vanier heard about. When ques-tioned, Jean Vanier told senior L’Arche leaders that he thought that the woman had been consenting. The woman herself agreed, sort of:

Was I consenting? I think at the beginning yes, but as time went on, the more I believe that I was not consent-ing.

A second woman came forward in March 2019, two months before Vanier died. Other statements came later. In total, there were six ‘allega-tions.’ The inquiry team is vague about what happened and even whether the statements were com-plaints or simply unaddressed personal issues. When you read the Report, the following key will help to understand the allegations in a more definitive manner. The Report makes numerous statements about the women, and it is rare for any state-ment to apply to all the women.

As only five women were inter-viewed, we will look at that group. The Report does not give numbers of victims to any statement but uses the words some‘’and s‘everal o’ften. When a group is constituted by only five individuals, it is easier to give precision to the words by using the following key: one‘’means one; some‘’means two; ‘several’means three; most‘’means four; and all’ means five. ‘

- ‘Jean Vanier had relationships with women…. A ’ ll (5) of the females involved were mature women, but only some (2) rela- ‘ ’ tions were inappropriate. ‘ ’

- ‘Several (3) of the women stated that they were vulnerable at the time.’

- While the Report says that Jean sexually assaulted the women, there is zero (0) basis for this in the women s quoted comments.

- ’ The Report does not suggest that drugs or alcohol were involved. Nor does the report mention any resulting pregnancy.

- ‘Some (2) of the sexual activity took place within the context of spiritual accompaniment.’

- At least one (1) woman said that Jean was tender. ‘

- ’ The authors judged that For some ‘ (2) of the women, these relationships were as coercive experienced and nonconsensual in nature’ (underlining added). To say that something is experienced is to ‘ ’ point to the fact that it is subjective. This at least suggests that all (5) women consented, i.e. did not say NO, leave the room, or ‘ ’ struggle – none (0) of which is mentioned in the Report.

- However, even if a woman did not object, she might still have been disturbed by the sexual approach. In fact, some (2) were disturbed ‘ ’ by it, either at the time or later.

- One woman said, I was frozen, I ‘ was unable to distinguish what was right and what was wrong. That ’ usually means that she was conflicted, caught somewhere between a YES and a NO. To be mature means to bear the responsibility of making decisions. It is not always easy.

To look at the women s statements ’ closely is like walking though the morning mist. The fog of judgmental jargon is lifted, and we see close-up the questions about meaning of their relationships with Vanier that lay in the women s statements. All the ’ women interviewed seem to have consented, but some had misgivings afterwards.

2. SEXUAL ABUSE: SPIRITUAL ACCOMPANIMENT

The Report avoids the vagueness of personal relations by focusing on one objective type of relationship, i.e. whether the victim was in a formal relationship with Jean called spiri- ‘ tual accompaniment. However, ’ only ‘some of the sexual activity took place within the context of spiritual accompaniment. The Report does ’ not explain spiritual accompaniment. It is not clear whether it was ever a formal program of L’Arche.

It is not clear whether training accreditation is required to give it, whether Vanier had received such accreditation and whether assistants were required to submit to spiritual accompaniment This accompani- . ment appears to have originated from Jean s days at ’ l Eau Vive ’ when he was thinking of the priesthood. A novice will regularly discuss with a superior whether he has a lifelong religious vocation. This appears not to be the case at L Arche, as Vanier complains ’ about the great turnover.

I discussed this relationship with a few experienced members of L Arche ’ in Canada. They told me that, when people came forward to assist the intellectual handicapped, Jean would explain to new ‘assistants’ (i.e. volunteers and staff) how to honour gifts of the intellectually disable, who were the ‘core members’ of L’Arche. Jean taught that the relationships between the core members and the ‘assistants’ could be mutually transformative; he would discuss with an assistant how he or she was experiencing this. Experienced members of L’Arche told me that accompaniment was a support service to assistants. It has not been explained as a psychological counselling session. If there were private latenight sessions at Jean’s place, such was typical of many college dorms at the time.

This suggests that Jean was sometimes acting as a leader of L’Arche and sometimes as another resident in the home. Spiritual accompaniment was never formal for Jean. This was just Jean’s personality. For half the period under review, i.e. anytime after 1980, Jean had no formal role in the leadership of the home but was an assistant like everyone else. the early years of In L’Arche, there were no directives preventing sexual intimacy between assistants. The Report spoke of other women who interacted sexually with Jean and not made allegations, even when prompted.

If there is a case to say that Jean Vanier was abusive of women, the L Arche Report was not successful in ’ making it. Perhaps Jean was a scheming fraud. Perhaps he was a ‘rock star’ of spirituality, knowingly using the weight of his fame and personality to force himself sexually upon women. Was he another Jim Jones, Charlie Manson, or David Koresh? This is really the central question, and in the final allegation, we get closer to the issue.

4. SEXUAL ABUSE: PSYCHOLOGICAL DOMINATION

The inquiry team said that Jean exercised a “psychological hold” on vulnerable women. That term refers to behaviour. The Report explains it as relationships which are emotionally abusive and characterised by significant imbalances of power, whereby the alleged victims felt deprived of their free will and so the sexual activity was coerced or took place under coercive conditions.

I find the phrase ‘felt deprived of their free will’ as a troubling evasion of culpability. Rather than focussing on the implied passivity of the women, it may be better to attest to misbehaviour on Jean’s part. We need to determine what behaviour would Jean need to have demonstrated for an objective person to label it abusive?

The term “psychological hold” is used by, and may have originated with, Maude Julien, a psychotherapist specializing in manipulation and psychological control. She has been working in this specialized area for more than twenty years and is an authority on this subject. Julien described the person with the hold as an ‘ogre’ who seduces his victim, then shames her by destabilizing her life, intruding in on it, and harassing and berating her. This sounds like what is meant by ‘emotionally abusive and characterised by significant imbalances of power.’ But that is not how people knew Jean. Read the words of Monsignor d’Ornellas, Archbishop of Rennes:

“We knew how close and attentive he was to each fragile person, especially people with disabilities. We have heard his prophetic word to put the vulnerable person at the center so that he can reveal to us our unsuspected treasures of humanity. We have witnessed his familiarity with the gospels and his friendship with the person of Jesus of whom he spoke to us.”

The Report confuses the technical term of ‘psychological hold’ with aspects that had nothing to do with Jean’s behaviour. One woman spoke of Jean’s fame (‘adored by hundreds of people’). Another said that Jean had a ‘charismatic personality.’ Neither of these is what is meant by ‘psychological hold.’

Many people – female and male – have met Jean and experienced a positive transformation in their attitudes. These people may say that he had transformed them and changed their lives for the good; this is not a ‘psychological hold.’ We must look at the evidence that the women gave us about Jean’s behaviour.

The Report presents (0) exam- no ples of domineering behaviour by Jean Vanier. (0) of the women None are quoted as saying that Jean abused them in a ‘psychological hold’ as described by Maude Julien. To be specific, (0) woman alleged that no Jean shamed her, destabilized her life, regularly intruded into it, and harassed and berated her.

Certainly, a person can act one way in public and another in private. However, the behaviour described by Dr. Julien would be hard to cloak from roommates over a 50-year period. However, not one of the other housemates has stepped forward to support the witnesses by verifying that Jean’s behaviour was often emotionally abusive. If Jean Vanier exhibited such behaviour, housemates would have noted it.

GCPS Consulting interviewed more than 30 non-victims, most of whom lived at L’Arche. However, no (0) such testimony is reported by any 3 party. There is no evidence that rd Vanier abused these women. The thousands of people across the world who have known Vanier over the decades do not recognize the sexual predator that is portrayed in the L’Arche Report.

A Cry Is Heard

Jean provided additional information on his relationship with Père Thomas (see ICN Autumn 2020.) in his final book, , A Cry Is Heard published in 2017. In it, Vanier makes several comments related to Father Thomas. Vanier says that it was the Holy Office in Rome that tasked him to run the spiritual formation house known as L’Eau Vive while Thomas was being investigated. Of this investigation, Vanier says only, “I later learned that Père Thomas had been disciplined by the leadership, but I did not know the real reasons for this decision, among the conflicting rumours that were circulating.”

Jean revealed that he was he had felt ‘pushed out’ of L’Eau Vive by that same Holy Office. “I had felt rejected by the Church that I desired to serve with all my being.” The friendship with Pope Jean Paul II salved his 50- year-old wounds; he felt accepted by the Church once again. Jean had gone to L’Eau Vive to determine whether he had a vocation. It appears that he was sent away thinking that he had somehow been at fault, but he did not understand what that fault was; that can be very painful. This underpins how communication can be fraught with miscues.

In a separate chapter devoted to Père Thomas, Jean discusses the Church’s second investigation of the priest’s sexual misbehaviour during a later period, i.e. during the 1970s and later. This investigation was more open than the first and the witnessing was graphic. In 2015, when Jean learned of the priest’s actions as reported by the women, he felt disbelief, shock, anger, and sadness in succession.

Jean concludes his reflections on Père Thomas by saying that he prays for the wounded – the women who were victims, the L’Arche communities, and Père Thomas himself. In that same chapter, Jean revealed that tensions arose between him and his former mentor as early as 1965. The disputes commenced over practical matters at first, then touched on matters of policy such as becoming open to ‘an ecumenical and interfaith dimension’ and welcoming women with intellectual disabilities into the home.

Finally, they fought over the governance of L’Arche. Jean realized that both he and Père. Thomas had to diminish to allow the community council to choose its own forward direction. The harmony which Jean once felt with Père Thomas fell away. Jean no longer took spiritual direction from the priest. As we know, Père Thomas set up his own house nearby. This home had a different house culture, but it would eventually be brought into line with the rest of L’Arche once Thomas retired.

Again, in that chapter, Jean revealed his own personal suffering and lack of confidence when he confronted the priest. L’Arche was experiencing great growth. The concept had ‘succeeded’ (his quotation marks). He wrote of his joy at what had been accomplished and of the guilt that he experienced for having feelings of personal pride. He spoke of his trials in leadership and the ongoing tensions with his former mentor, but also the sense that he had grown personally through all this.

He concluded his assessment of this period by saying: ‘I was driven by a need for action and the desire to preserve unity in L’Arche.’ This is admirable. However, one’s good works should not cover up one’s failure to fulfill one’s duties. These comments were made immediately before speaking about the women’s witness against the priest. Jean was troubled that he may have failed in his dealings with Père Thomas. Despite all the things that Jean did accomplish, he was now crossexamining his conscience about what he was accused of not having done.

The Breakdown

Stephan Posner, International Leader of the L’Arche network, was interviewed by KTO-TV in France. The interviewer asked: “Did the women who came forward to make statements say anything about how we are to understand who Jean Vanier was as a person?” Posner could not answer her question. He admitted his lack of understanding. He said that people at L Arche will continue ’ to ponder the early years of L Arche. ’ What is clear is that the L Arche Report is not a judgment on Jean Vanier. Rather, it is the expression of the views of individuals, and a judgement that the allegations were serious. There was no trial, no defence, and no testing of the evidence. While the authors do not claim that there was a trial, they do leave the impression that no one could contest their judgments.

The allegations are phrased by the report writers. The witnesses cannot be questioned about how well the report reflected their experiences as the women are unidentified. We are not told that the women s stories ’ were submitted anonymously, only that the report s authors chose to ’ keep them anonymous. Such accusations should not be made anonymously.

When only an organization s’ leaders are aware of misdeeds, their ‘ ’ corrective actions may be totally inadequate. Witness the case of former Cardinal and Archbishop of Washington, Theodore McCarrick, who got away with sexual crimes against adults and minors and with abuse of power for decades because the institution of the Church kept the allegations against him anonymous.

L Arche should seek the women’s ’ consent to release their stories of their interactions with Vanier. This assessment of the L’Arche report on Jean Vanier explains it as a communication to distance the federation of care homes from some rumours that had begun to seep out. By putting out this report, L’Arche International was protecting individual homes from any backlash resulting from the spread of these rumours, such as the statements made by AVREF. L’Arche is not the appropriate institution to judge the allegations any more than to defend Jean Vanier against allegations of sexual misconduct. In this inquiry, L’Arche acts as investigators, prosecutors, judge, and jury. However, L’Arche itself may bear some responsibility for lack of oversight or even willingness to turn a blind eye to allegations.

This may have been because there was no policy and structure in place for women to seek guidance against senior house members. L’Arche is in the process of correcting that. As always, more could have been done sooner. Because of their potential complicity, any investigation into Jean Vanier by L Arche cannot be ’ considered as impartial.

Nor was there any audit performed on the Report and its supporting data to confirm that the findings were justified by the evidence. The Oversight Committee reviewed the investigative process and the findings but did not have access to the raw data.

The Report itself lacks rigour. Any guilt is based upon association, innuendo, misdirection and bafflegab about mysticism and psychology. The Report does not tell us the stories of the women. The Report provided no evidence that Jean sexually assaulted or harassed women, although it is clear that he puzzled some.

The Report makes criminal accusations but wants not to bear the burden of having to prove them ‘beyond any reasonable doubt,’ the appropriate standard for such allegations. The language of the report is slippery. They say that their report is based upon the “balance of probabilities.” However, there is no advocate on Jean s behalf and no ’ attempt to provide balance. This is a one-sided assessment.

Walter Hughes, Ottawa