St. Francis and The Wolf of Gubbio

Ed Debono, OFM Conv., Kingston, ON

Volume 39 Issue 7, 8, & 9 | Posted: October 19, 2024

Here is the background of the origin of the painting.

There is a story of the Wolf of Gubbio in the annals of Franciscan literature. A wolf was ravaging and harassing the people of the town of Gubbio, Italy. Francis was informed about the situation and decided to meet the wolf. Francis encountered the wolf and realized the wolf was frightening the people because he was hungry.

Francis entered into a covenant with the wolf that if the town’s people fed him, the wolf would not ravage them but be at peace with them.

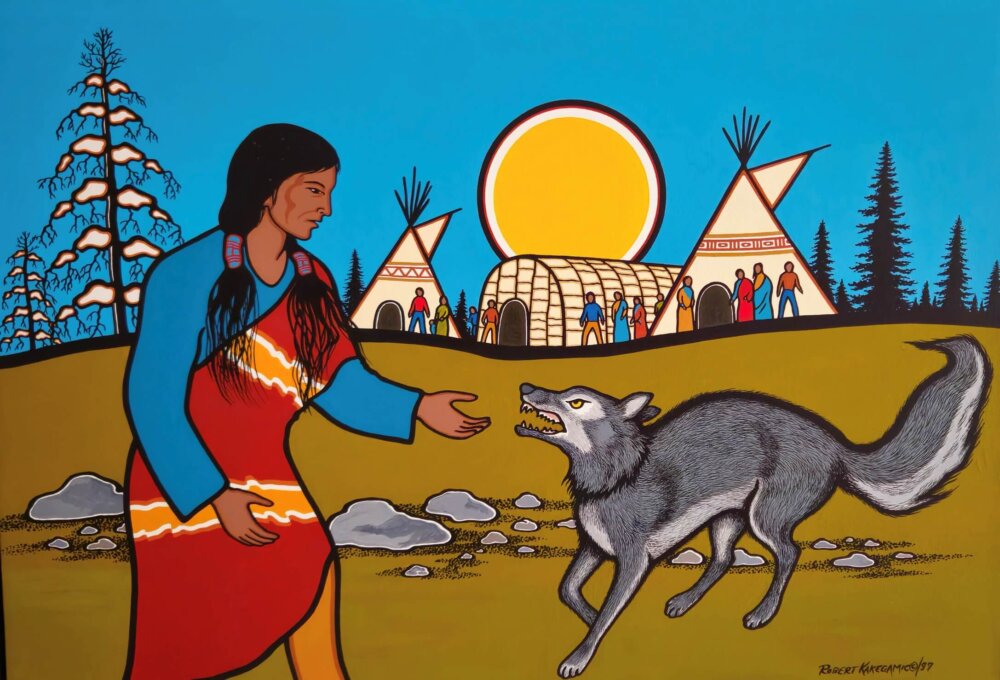

The painting of St. Francis of Assisi as an Indigenous wisdom person encountering the wolf of Gubbio, was painted by Robert Kakeganick, a Canadian Indigenous artist.

The painting was commissioned by Friar Philip Kelly, OFM Conv. (of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual). Date unknown.

It exemplifies St. Francis’ mission as a person of peace and reconciliation.

The fully developed story first appeared in the Actus about a hundred years after St. Francis died. A mid-thirteenth-century chronicle of the Benedictine Monastery of San Verecondo at Vellingegno between Gubbio and Perugia supplies the following undoubtedly genuine text (AFH 1, 69-70):

In recent times the poor little man St. Francis often received hospitality in the Monastery of San Verecondo The devout abbot and the monks welcomed him with pleasure…

Weakened and consumed by his extreme moritifications, watchings, prayers, and fasting, St. Francis was unable to travel on foot and was carried by a donkey when he could not walk and especially after he was marked with the wounds of the Savior.

And late one evening while he was riding on a donkey along the San Verecondo road with a companion, wearing a coarse sack over his shoulders, some farm workers called him, saying: “Brother Francis, stay here with us and don’t go further, because some fierce wolves are running around here, and they will devour your donkey and hurt you too.”

Then St. Francis said: “I have not done any harm to Brother Wolf that he should dare to devour our Brother Donkey. Good-by my sons. And fear God.”

So St. Francis went on his way. And he was not hurt. A farmer who was present told us this.

Another early text that may or may not be relevant is the testimony of Bartholomew of Pisa in his Conformities 1399) that on Mount Alverna St. Francis once converted a fierce bandit. The local tradition adds that he was called Lupo (wolf) because of his savage cruelty, but that the Saint renamed him Agnello (lamb). He is reported to have become a holy friar. It was due more to him perhaps than to the wild animals that explored the mountain in 1213 (LV, pp. 270-74). Could this Fra Lupo have been the Fra Lupo who accompanied St. Francis on his journey to Spain in that year and who died in Burgos in 1291 (W1219, n.19)?

Late in the nineteenth century the wolf’s skull, with its teeth firmly set in the powerful jaws, was reported to have been found in a small shrine on the Via Blobo which was said to be over the wolf’s tomb. A stone on which St. Francis preached to the people after converting the wolf is shown to visitors in the Church of San Franceso della Pace.

Finally, in January 1956, press dispatches reported that packs of famished wolves were once again terrorizing villagers in central Italy.

In a letter dated February 8, 1958, the distinguished Conventual historian Giuseppe Abate writes that he is preparing a brief study of the incident based on original research in local archives, and that he considers it “probable” owing to the “great weight” of the 1290 reference, though “perhaps a little embellished” in the Actus.

Ed Debono, OFM Conv., Kingston, ON