Sensitization, Then Action: Trust Challenge for Faith Communities

Monica Nelson, Victoria

Volume 35 Issue 4, 5 & 6 | Posted: July 8, 2021

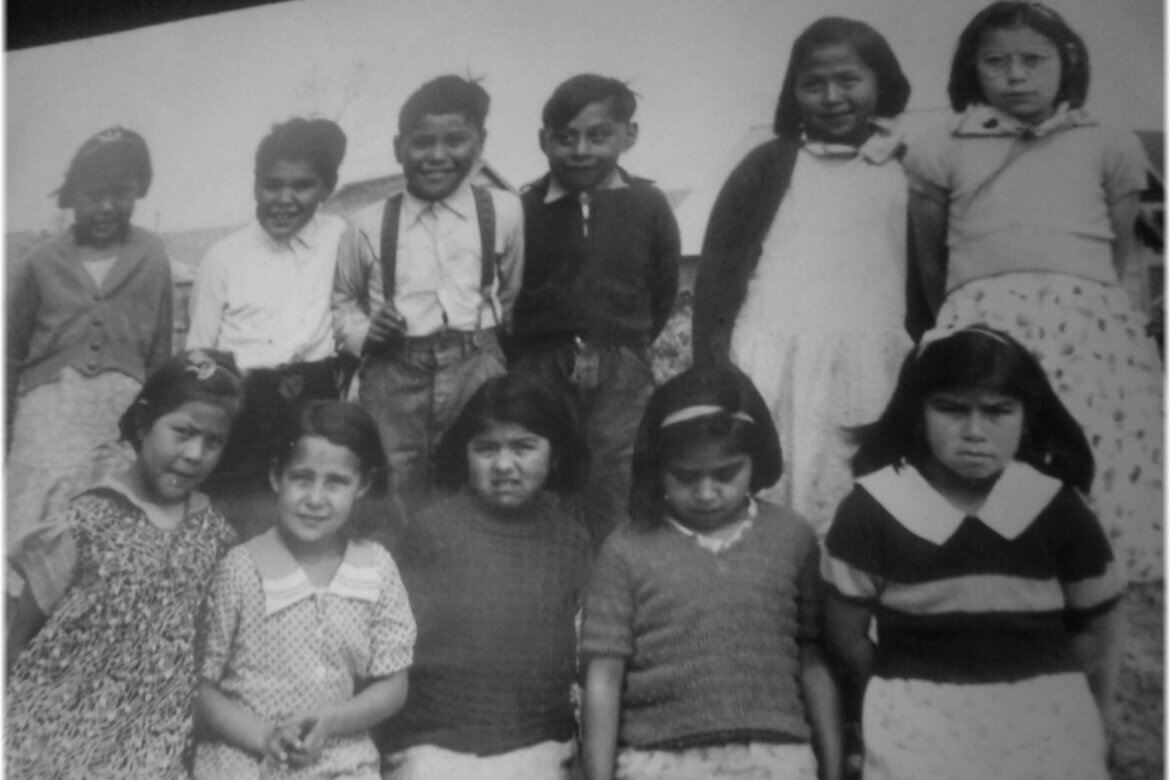

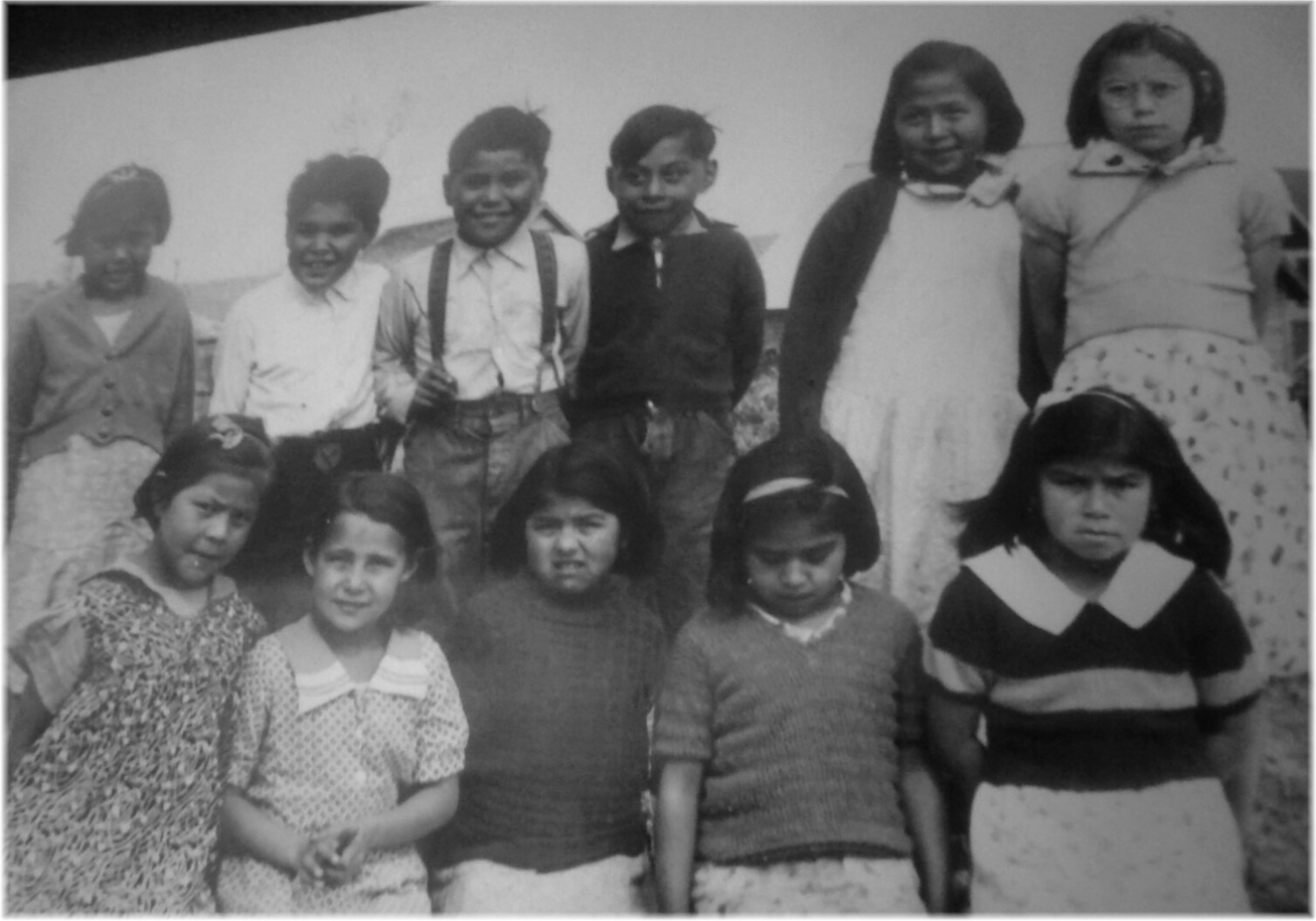

The impact of trauma and abuse can take years to heal even with supports in place. When enough healing hasn’t occurred, the wounds readily become intergenerational as is the situation with those who attended Canada’s residential schools.

The recent discoveries on residential school grounds of shockingly high numbers of unmarked graves (not mass graves), has put many into a state of horror and despair. First Nation communities weren’t surprised however, nor those following the TRC reports.

Though the gravesites will contain some who weren’t attending the schools, the thought of so many lost children has finally pulled the broader community into a desire to understand the struggle faced by many of First Nation heritage. Like the searing image of the Syrian boy found drowned on the beach, the time of awakening has come.

Our understanding of the terrors of the residential school system resonates more deeply now after nearly two years bound by the pandemic. Our frenetic lifestyle was curtailed, we’ve had much more time with our children and our appreciation of the gift of family, has been heightened.

Covid-19 became this overarching and unknown monster that turned our lives upside down. We’ve felt the pain of isolation and a loneliness so intense that mental health issues have soared. Depression, physiological impacts, waves of fear, denial, confusion, misinformation and concern over vaccines has been in our thoughts both day and night.

Our religious gatherings were abruptly stopped, we’ve been separated from families and friends, missed touchstone celebrations and lost loved ones without being able to say good-bye. Even our identities started disappearing under masks and a pervasive ache just to be hugged, became commonplace. And in this overall state of anxiety, we’ve also seen an alarming rise in issues of abuse.

2.

The question is, now that we’ve been sensitized, will society continue to be interested? One part of society will. Although faith communities were already engaged with First Nation groups before the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (2007), the relationships broadened with the start of the 2008 Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Despite news reports to the contrary, there has already been an apology from the pope in 2009, when Pope Benedict met with First Nation leaders.

In a CTV news report (April 29, 2009, updated May 18, 2012), Edward John of the Tlazten First Nations said at the time that he hoped the apology would help “many people move forward.” “To listen to the Holy Father explain his profound sorrow and sadness and to express that there was no room for this sort of abuse to take place in the residential schools, that is an emotional barrier that now has been lifted for many people,” he said.

Phil Fontaine, the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations in 2009, commented that what he had heard, gave him “great comfort.”

3.

This may be surprising to those who didn’t pay that much attention before but now feel the need to after the recent news regarding the Kamloops and Marieval Indian Residential Schools.

Many denominations in Canada have worked tirelessly alongside First Nation communities to address the pain and to create new and healthy relationships, whether specifically in Christian terms or in ways specific to First Nation traditional beliefs. They have given sincere and deeply felt apologies for those members who abused residents in anyway. But these efforts have been done and continue to be done, without fanfare in the broader community. The focus has been to help with healing.

On a more public scale, the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement involved the Government of Canada, the religious organizations that operated the schools and well over 80,000 Indigenous peoples in Canada who had been enrolled in the Indian Residential Schools. And the settlement acknowledged the grievous harm inflicted by the Residential School System. It was the largest class action settlement in Canadian history at that time.

Several denominations put their very continuance as faith communities at risk to beginning paying their portion of the settlement; the government only agreed in 2017 to include the residential school survivors from Newfoundland and on June 9th of this year, the Federal Government proposed a settlement for the day school students who attended Indian Residential Schools. The process has been complicated and ongoing.

To some, there is the idea that the Pope sits in Rome, pulling strings on peoples around the world. Not so. The general public isn’t aware nor interested in the workings of a church unless part of one. For Catholics in Canada, the structure is decentralized. Each Diocesan Bishop is autonomous in his own diocese. He is in relation to the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops but is not accountable to it. In other words, in terms of the residential schools, the pope was not involved.

Nevertheless, Pope Benedict recognized the compassionate need to acknowledge and apologize for the abuse of the First Nations in Catholic run Residential Schools and Pope Francis will finally be able to meet with First Nations delegates, later this year. The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops have been working with Elders/Knowledge Keepers, residential school survivors, and youth from across Canada for over two years to plan this meeting. If not for the pandemic, the meeting would already have occurred.

For any survivors of trauma and abuse, an overriding mistrust can be strong. Creating new and right relationships with First Nations Peoples will continue to be a complicated process. Everyone is at a different place in their healing, intergenerational trauma has its own unique aspects and those who abused the children would no longer be living, including those in the Federal Government who created, designed, financed and enforced the attempt to completely annihilate First Nation cultures.

If we are to successfully go forward, all Canadians must be part of this process and not only for a month or two.

Archbishop Gerard Pettipas once stated, “Reconciliation is about relationship.” And that comes by developing trust and sharing truth, on all sides. Burning down churches may give a short term sense of power and relief but the pain will remain and now more people, including First Nation members, have been wounded again.

Chief Cadmus Delorme of the Cowessess First Nation, has taken a more positive and healing step forward. Despite the overwhelming number of unmarked graves on the Marieval Indian School site, after a private gathering of families, friends and those still haunted by the memories of the school, another gathering was prepared.

This time, on June 26th, the public was invited to join the First Nation community at the gravesite so all could grieve this heartbreaking discovery together. Together as a country, Canada mourns.

Let us continue then, to walk this path, getting to know each other, uplifting the wounded ones and embracing forgiveness as we carefully work through the history of a cruel and racist system. To move forward as a nation, this journey can no longer be avoided.

Monica Nelson, Victoria