James A. Teit’s Anthropology of Belonging

Editorial Essay by Patrick Jamieson, Victoria

Volume 35 Issue 7, 8 & 9 | Posted: October 4, 2021

As a progressive Catholic newspaper, one might assume ICN is in a bit of an awkward situation regarding the residential schools revelations as liberally exposed by the mainstream media in particular the CBC, the country’s national public broadcaster.

I suppose that on some level we are expected to defend the institution of the church out of sheer loyalty. As I have said on other occasions of controversy, the church is big enough to look after itself. On the progressive side of the church, beyond the usual liberal hand wringing, there is a more radical perspective and analysis to be sought by sifting through the entrails of the situation. Phil Little’s exhaustive reflection (see the Main Feature: “Residential Schools: Conjectures of a Guilty Former Oblate) gets all that off to a good start.

Personally, I have been busy with a sort of digging in during a pandemic election call and the ramifications of Afghanistan. At the same time I finally get to use the term ‘full disclosure’ with the facts that my father was Indigenous from Kamloops. He didn’t go to residential schools as his indigenous father went ‘the White Man’s route,’ as he used to state it, becoming a conductor with the Canadian Pacific Railway and dying at age 71 from the ultimate effect of a train accident.

My father was the third of four boys, he was 13 when his father died. His mother was of Dutch origin, twenty years younger than John Alexander, and she had her hands full running herd on four boys, age ten to nineteen after her husband’s death, leaving her two small houses on Battle Street in Kamloops, with which to make ends meet.

Asked occasionally if he experienced racism and prejudice growing up, by one of my more enquiring brothers – either the military social worker or the lawyer – “well, we were called dirty little Indians,” he would invariably say almost with a level of bemusement.

2.

Ours was a matriarchal family with the emphasis upon the English Irish argumentative atmosphere focussed on current events at the supper table conversation. Our mother was addicted to newspapers and listening to CBC radio. My father would enjoy the clatter, proud of all his kids, but would hardly say a word, nor get up from the table once he sat down. “While you are up” was his most favoured quotation, ‘would you get some more gravy from the kitchen.’ Arguing or contradicting held no appeal for him, I cannot remember him criticizing anyone even people who cheated him in business.

He died nearly five years ago now, well into his 95th year. A military veteran of nearly 40 years, at age 55 he retired to open a watch repair jewellery story and significantly look after the other guy and the little guy in the form of general welfare concerns and, most predominantly, by sponsoring refugees from every continent during the next 40 years. He always referred to Canada as ‘this great country,’ and he’s generally considered a contemporary Catholic saint in the community.

I could go on more about him, but you get the general idea.

3.

Meanwhile back at the ranch, other developments were transpiring. Boothroyd reserve is in the region of the Fraser Canyon in B.C., which runs from Lytton to Spences Bridge including Boston Bar and North Bend. This is where my father used to spend summers with First Nations relatives. One cousin family had eight or nine attractive sisters, so he was quite attached to that group. Even after he retired to Victoria in 1976.

The Fraser Canyon area is the home of Interior Salish Nation. The historic conventional term used is Thompson Indians named after the river where they derived their sustenance and sustained existence.

James Alexander Teit published his extraordinary studies and memoirs of these people and that area in his 1900 published study under the title The Thompson Indians of British Columbia. It was published under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History, edited by Franz Boas, a noted anthropologist. The back cover blurb reads:

“The following description of the Thompson Indians is based on two manuscripts by Mr. James Teit – the one a description of the Upper Thompson Indians written in 1895 and the other a description of the Lower Thompson Indians written in 1897. Mr. Teit is fully conversant with the languages of the Thompson Indians, and owing to his patient research and intimate acquaintance with the Indians, the information contained in the following pages is remarkably full.”

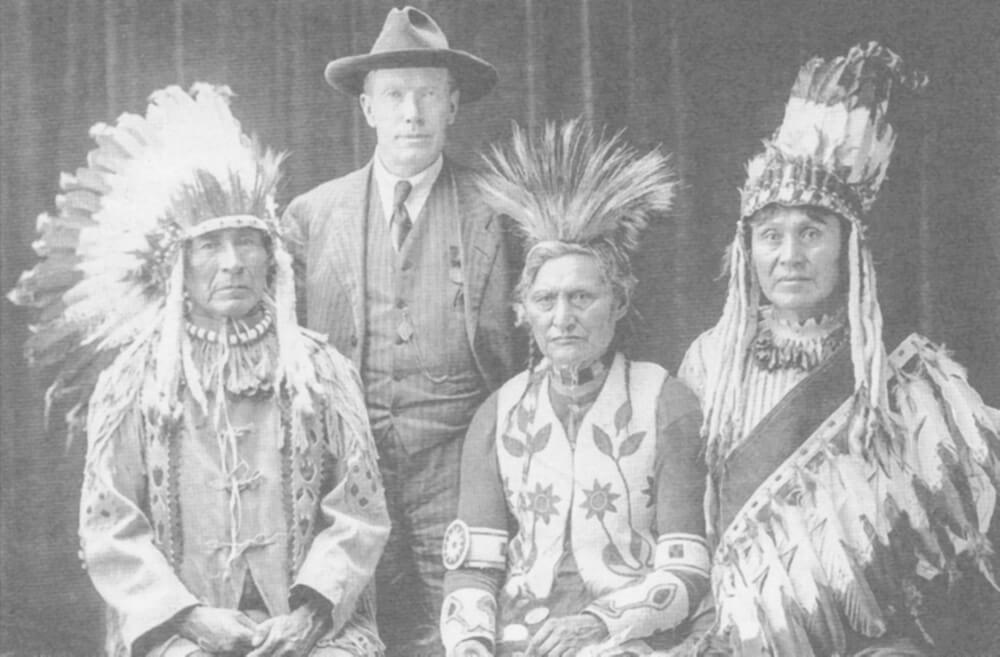

So who is this James Teit who lived amongst the Thompson for decades and was so respected by the BC Chiefs that he was a representative in their delegations to Ottawa negotiations?

UVic history professor Wendy Wickwire’s 2019 book At the Bridge – James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging is a spellbinding account of this Scottish immigrant. She sees him as a champion of Indigenous rights.

The blurb on the back cover outlines it well. “Every once in a while, an important historical figure makes an appearance, makes a difference and then disappears from the public record.

“James Teit (1864-1922) was such a figure. A prolific ethnographer and tireless Indian rights activist, Teit spent four decades helping British Columbia’s Indigenous peoples in their challenge of the settler-colonial assault on their lives and territories.

“At the Bridge chronicles Teit’s fascinating story. From his base at Spences Bridge, Teit practiced a participant-based anthropology that covered much of B.C. and northern Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana.

“Whereas his contemporaries, including famed anthropologist Franz Boas, studied Indigenous people as the last survivors of ‘dying cultures’ in need of preservation in metropolitan museums, Teit worked with them as members of living cultures actively asserting jurisdiction over their lives and lands. At the Bridge lifts this story from obscurity.”

Teit obviously represents a sort of model for these times. Happily for my purposes, he happens to have manifested his life and work in precisely the area and times of my family’s immediate ancestors as a People. The identification of Mr. Teit and his works was done by one of my siblings, three of whom have taken out their First Nations status to help with their life’s work.

One works in an Aboriginal Nursing home in Winnipeg, another is part of B.C. Indigenous Judicial Association and the third, who provided the books on and by James Teit, is a theologian in Montreal teaching First Nations Spirituality and doing research in the Fraser Canyon during sabbaticals.

4.

As a sample of Teit’s work, from page 175 of his book The Thompson Indians of British Columbia, published in April, 1900, there is the section POPULATION. It gives evidence of his overall tone and attitude:

“The tribe is at present greatly reduced in numbers. The existence of numerous ruins of underground houses might be considered as sufficient proof of the decrease of the tribe, were it not that the same family sometimes constructed several of these houses, and that after the first epidemic of small-pox many of the survivors moved for protection or support to larger communities, and constructed new houses there …

“The old people say that forty or fifty years ago, when travelling along the Thompson River, the smoke of Indian campfires was always in view. This will be better understood when it is noted that the course of the Thompson River is very torturous, and that in many places one can see but a short distance up or down the river. The old Indians compare the number of people formerly living in the vicinity of Lytton to “ants about an anthill.”

“Although they cannot state the number of inhabitants forty years ago, there are still old men living who can give approximately the number of summer lodges or winter houses along Thompson River at that time, showing clearly the great decrease that has taken place.

“In 1858, when the white miners first arrived in the country, the Indian population between Spuzzum and Lytton was estimated at not less than two thousand, while at present it is probably not over seven hundred. If that be correct, and assuming that the number in the upper part of the tribe was in about the same proportion to those in the lower now, the population of the entire tribe would have numbered at least five thousand.

“Notwithstanding the fact that a year or two before the arrival of the white miners the tribe had been depopulated by a famine, which infested nearly the whole interior of British Columbia, the actual decrease of the Indians has taken place only since the advent of the whites, in 1858 and 1859.

“Small pox has appeared but once among the Upper Thompson Indians but the Lower Thompson state that it has broken out three or four times in their tribe. Its first appearance was near the beginning of the Century. Nevertheless this disease has reduced the numbers of the tribe more than anything else. It was brought into the country in 1863, and thousands of Indians throughout the interior of British Columbia succumbed to it. If the evidence of the old people can be relied upon, it must have carried off from one fourth to one third of the tribe.

“In many cases the Indians became panic-stricken, and fled to the mountains for safety. Numbers of them dropped dead along the trail; and their bodies were buried, or their bones gathered up, a considerable time afterwards. Some took refuge in their sweat lodges, expecting to cure the disease by sweating, and died there.

“It was early in the spring when the epidemic was raging, and most of the Indians were living in their winter houses, under such conditions that all the inhabitants were constantly exposed to the contagion. The occupants of one group of winter houses near Spences Bridge were completely exterminated; and those of another about three miles away, numbering about twenty people, all died inside their house. Their friends buried them by letting the roof down on them. Afterwards they removed their bones, and buried them in the graveyard.

Since then the tribe has been gradually decreasing, until at present I doubt if it numbers two thousand souls. About fifteen years ago it was reckoned by a missionary long resident among them as numbering about twenty five hundred.

“Many suppose that the decrease among Indian tribes in general is chiefly due to the dying off of the old people and to the sterility of the women. My observations lead me to a different conclusion, at least regarding to the Upper Thompson Indians. There are comparatively few sterile women among them.

“The following statistics concerning the Indians of Spences Bridge will serve as an illustration of the decrease of the Indian community. They were collected by myself, and extend over a period of ten years….”

5.

Teit’s book consists of 250 pages of such detail and analysis, a veritable treasure trove of a lifetimes dedication to his anthropology of belonging.

Editorial Essay by Patrick Jamieson, Victoria