The True Story Behind ‘Jesus Revolution’

A film review by Paul LeMay, Vancouver

Volume 38 Issue 4, 5 & 6 | Posted: July 11, 2023

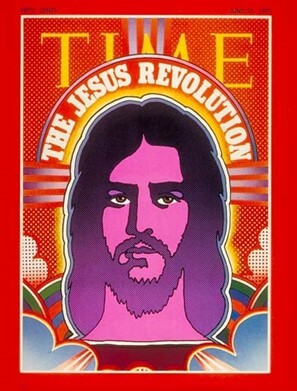

A quick synopsis: The true story of a national spiritual awakening in the early 1970s and its origins within a community of teenage hippies living in Southern California. The film’s title was derived from an original Time Magazine cover story that came out June 21, 1971. The film version, released on February 24, 2023, stars Kelsey Grammer as the minister of a rather staid protestant church in California, Jonathan Roumie as the itinerant free-spirited hippy preacher and Joel Courtney and Anna Grace Barlow as the messed-up teens looking for answers.

As a 15-year-old high school kid at the time the original Jesus Revolution article appeared in Time Magazine, I can attest from first-hand experience that the cover’s artwork, reminiscent of Peter Max’s Yellow Submarine film for the Beatles, definitely captures some of the feel and flavor of those heady times. Indeed, as I recall, my parents actually subscribed to Time at the time.

I also remember those times as a church-going Catholic who took part in what our French-language parish then called “La messe des jeunes” (or “The Young People’s Mass”). The “radical” alternative service took place in the church basement concurrently with the more conventional Mass upstairs which continued to be draped in its rather dull and droning organ music, at least that’s how it sounded to the ears of a teen used to hearing rock and folk music on the radio.

By contrast, our hipper services not only involved folk guitar, the celebrants, usually involving a younger priest assisted by a younger nun wore civies. To this day, I can still recall our congregation of budding long-hairs being handed the lyrics to Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water, and then quietly listening to the song together, and then “rapping” about it all. (And yes, rapping at the time meant talking about what we thought the song writers meant.)

This missive was then followed by scripture readings for that Sunday in the liturgical year that thematically matched the song lyrics we had just considered. The connections were self-evident. It was, to say the least, a very effective approach to use with young people. Sadly, many of the parents upstairs didn’t see things that way. They didn’t like the idea of their kids taking part in what my dad derisively called “The Hippie Mass”.

And so before long, the whole promising experiment was dutifully shutdown by the Blue Meanies upstairs. But in some sense, it was too late. We had come to understand that our parents were more interested in keeping us within the conformity mode of their own thinking than in allowing us to find our own spiritual way through the rapidly reshaping world that was the 1960s. Result?

Most of the kids I knew, me included, simply stopped going to church, despite our parents’ wishes and repeated prodding. Little could they appreciate that this new Baby Boom generation simply found the conventional church’s approach to spirituality to be entirely irrelevant to their lives.

The Jesus Revolution film not only did an excellent job capturing these same sentiments, it also addressed many of the other related themes present in that era. Indeed, I was happy to see the film’s writers didn’t duck all of the drug experimentation that was going on then, but instead went at the question head-on. I know I certainly saw the same thing going on all through the 1970s within my own circle of friends then.

What the writers also got right, as was voiced by the young upstart street preacher character Lonnie Frisbee, was that beneath all of the drug-taking was a thirst for spiritual answers. That argument certainly resonated with me, both then and now. To my own mind, the desire to escape the existential pain and emptiness of a world obsessed with material consumerism helped fuel my generation’s willingness to experiment with mind-altering substances – a theme that’s just as valid today as it was then.

At present, drug-taking is still seen as a cool thing to do when you’re a teen, as evidenced by teen use of the party rave drug ecstasy (a.k.a. MDMA). And it hasn’t helped that our culture has actually become even more permissive around the whole drug-taking proposition. One need only look at the legalization of cannabis use in Canada in recent years, and now the British Columbian government’s willingness to permit the use of several much harder and more addictive substances, such as heroin and cocaine.

And this doesn’t even touch on the fashionable use of various “plant medicines” such as ayahuasca and psilocybin in both new-age and traditional native vision quest circles. But even these can only offer a temporary reprieve for what ails us, namely the unrelenting sense of separation from our soul’s undying spiritual source, our divine Creator.

This is part of the larger love message that is on abundant display in this film. Our indwelling connection to God isn’t something we need invent, nor is it something we can buy. It patiently waits inside us for the day we suddenly decide to pay serious attention to the reality of the divine omnipresence. All we need do is genuinely surrender the hubris of our ego’s ultimate powerlessness in the face of God.

While I certainly found the film to be both an uplifting and a tearfully inspiring experience, the only deficiency I found was what I have long known and observed in our western approach to religion, namely, an over-emphasis on scriptural teachings while engaging in a rather feeble hit-and-miss approach when it comes to Christ’s experiential examples as teachings.

As deeply meaningful as scripture-based teachings are, how western religions tend to convey our Lord’s experiential lessons generally fall well short of any clear articulation of which techniques we should use to implement these experiential examples. We speak of Jesus’s 40 day fasting journey into the desert, and his prayerful meditative periods on hill tops or secluded in a garden where He could recharge his spiritual batteries after a long day of teaching and healing in his community. But when do we say, we too need to integrate such practices into our lives as part of our own daily spiritual practice? On this score, the institutional versioning of Christ’s church remains sadly wanting.

And yet the Christian tradition is abundantly rich with a contemplative and meditative tradition that speaks to this very question. But even to this day, these traditions receive little more than polite lip service in our various mainstream Christian denominations, and little effort is made to see that we integrate them into our daily spiritual practice.

So, as much as I loved this film, and I did love it, I nonetheless came away from it feeling like I was slightly short-changed on this score. That’s not the fault of the film or filmmakers of course. They were simply trying to faithfully retell an original true story that took place in Southern California.

But the film reminded me of one glaring short-coming that our mainstream churches continue to perpetuate: an absence of teachings about the importance of our own inner contemplative lives in cultivating our own relationship with the divine. This for me remains a critical dimension of Christ’s teachings.

As such, I feel it is well past time for our churches to start teaching and integrating practices like meditation into their congregational assemblies. To do no less reminds me of the days when my own parents could not hear the needs of their own kids when it came to the relevance of the Young People’s Mass in the very period that this film is about.

Paul H. LeMay, BA (Psych) is a long-time ICN contributor, and the co-author of “Primal Mind, Primal Games: Why We Do What We Do”

(https://www.primalmindprimalgames.com)

A film review by Paul LeMay, Vancouver