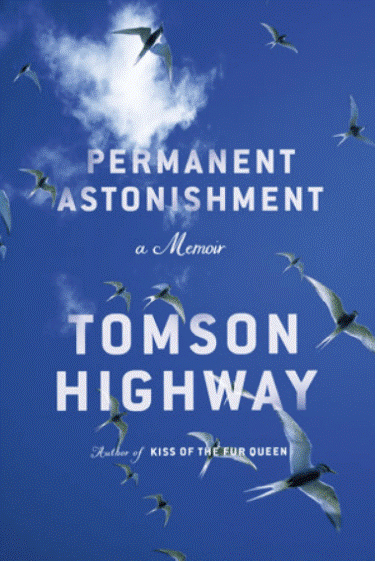

Permanent Astonishment – Showing a Way Forward

Peter Best, Sudbury, ON

Volume 37 Issue 1, 2 & 3 | Posted: April 6, 2022

After a press interview several years ago Tomson Highway, author of Permanent Astonishment (Doubleday Canada, 2021) found himself sidelined by Indigenous and media elites for his apostacy in saying that some good things came out of residential schools. He said:

Nine of the happiest years of my life were spent at that school…You may have heard stories from 7000 witnesses that were negative. But what you haven’t heard are the 7000 stories that were positive stories. There are very many successful people today that went to those schools and have brilliant careers and are very functional people like myself. I have a thriving international career, and it wouldn’t have happened without that school. You have to remember that I came from so far north and there were no schools there.

Permanent Astonishment puts hopeful and inspiring flesh on this assertion. In its loving portrait of his parents, his family, his friends, his classmates and teachers at residential school, of meeting the challenges of the harsh but beautiful wilderness he grew up in, Permanent Astonishment is a work of transcendental, universalist power. Like all works of art, if only during the startling, “astonishing” moments when the reader is in the near-ecstatic grip of it, it transcends superficial boundaries that divide us as humans and that dangerously separate us from nature. It acknowledges failings and wrongs, (One priest fondled young boys in their dormitory beds), but urges that they should not be life-defining.

Permanent Astonishment is overflowing with stories and anecdotes about diverse human characters humorously and generously portrayed, Indigenous food and recipe descriptions, and botanical, zoological, and geographic details of the wilderness world of his childhood. Its warm and capacious nature lifts the reader out of his getting and spending reality and takes him to a better place – the human soul-enriching world where the truth that all humanity is an interconnected whole is realized and felt.

Tomson is joyfully gay –“two-spirited”– and he sensed it from very early in his life. He says that he only had one godparent, a woman, “one reason for the pronounced femininity of my persona.” He writes of his father’s total acceptance of this:

When I think back to it, even the fact that I am a “girl” does not faze Dad. He sees me playing “girlie” games – putting on Mom’s apron for example, and pretending it’s a skirt- but to him, it makes no difference…Where too many men would beat the woman out of their effeminate boys to turn them into “men”, thus destroying the lives of those boys, the lives of their families, and most blindly, their own, the world’s most athletic, most masculine man, world-champion dogsled racer Joe Lapstan Highway, loves me even more.

Joe Highway was a fisherman, bushman, dogsled champion, devout Catholic, tireless laborer, faithful husband to Balazee, with no formal schooling and unable to read and write, father of twelve children, of which Tomson was the eleventh, gave this remarkable gift of unequivocal love and acceptance to this son of his, and allowed him to be the individual he was born to be: classical pianist, playwright, author and two-spirited, transcendentalist trickster funny man.

Humanity’s unhealthy and dangerous break from nature is a growing threat to our existence. Permanent Astonishment, with its chapters alternating between descriptions of the author increasingly being happily gripped by non-Indigenous “civilization” at his residential school, on the one hand, and his vivid descriptions of his life and soul-defining experiences in the wilderness during the summers of his youth, exemplify this dichotomy.

With the advance and ultimate dominance of European civilization in Canada the distant forefathers of today’s Indigenous Canadians lost their old way of life forever. Their generation, as the author writes about Joe Highway’s, “leaped five generations in one.” The reserve system and the Indian Act, the establishment of which has to be seen in hindsight as a big mistake, set up a system designed to ensure the failure of Indigenous Canadians to adapt to the new reality that had tragically overwhelmed them. This state of general failure continues today.

Tomson Highway and Permanent Astonishment possess the inherent sweetness to stop the poisonous leak of useless bitterness, divisive demands and false accusations against their fellow Canadians that continually emanate from Canada’s Indigenous elites, and which are shamefully acquiesced in by our non-Indigenous elites.

Permanent Astonishment is rich with the virtues of gentleness, forgiveness, gratitude, and kindness.

He thanks Sister St. Aramaa for giving him the gift of the piano. He thanks his 200 classmates “for all they have given me all these years – companionship, laughter, and yes, love, in all its richness. I love them to death. I love them to pieces.” He forgives his classmate Stanley Blackbird who punched him on the side of the head because he was a “sissy”. He compliments his staff and teachers; “kind” Mrs. Rasmussen, “kind” Mr. Bouchard, and thanks them all.

The brilliant trans-gender, two-spirited Welsh writer, Jan Morris, born James Morris, who experienced all manner of human dysfunction in his/her long life, summed up her view of life in one of her last books, Thinking Again, this way:

“Worst of all (the problems of the world) though, has been the way humanity has turned upon itself…We have no certainties anymore, no heroes to trust, no Way (in mystic capital letters) and no Destination. But perhaps you will forgive me, if I propagate an old thesis of my own once more. It is this: that the simplest and easiest of virtues, Kindness, can offer all of us not only a Way through the imbroglio, but a Destination too.”

The kind, tolerant, forgiving, forward-looking, and celebratory Permanent Astonishment shows not only a Way through the Indigenous-non-Indigenous imbroglio bedevilling Canada today, but it shows that a united, race-free Destination is possible.

Mr. Highway writes that he is dedicating his life to dismantling “that hateful, destructive two-gender structure that arrived on our continent in 1492.” But if the old social rigidities around sexuality and gender identification should be loosened, shouldn’t the old social, political, and legal rigidities around race in Canada be loosened as well? Shouldn’t “race” become equally irrelevant? Permanent Astonishment suggests an affirmative answer to that important question.

Peter Best is a Sudbury lawyer and the author of “There Is No Difference: An Argument for the Abolition of the Indian Reserve System”, which has been endorsed by retired Supreme Court of Canada Justice Jack Major.

Peter Best, Sudbury, ON